Risk of Indirection

Published by Weisser Zwerg Blog on

Risk involved in acquiring legal titles via a service provider.

Rationale

In cases where you acquire legal titles (shares, money deposits, insurances, …) via a financial service provider there are several risks associated with the service provider that I feel are mostly overlooked. In this blog post I try to outline a systematic approach via which you can identify such risks and find ways on how to mitigate those risks.

I call these risks risks of indirection. Most likely there exists a technical term that I am not aware of. I tried to search for these types of risks via

Google, but without success. If you know the technical term I’d be very much interested. Please let me know.

The risks are real

Only after developing this blog post and its systematic approach I found the story behind sparpiloten (the associated web-sites are offline by now: sparpiloten.ch/sparpiloten.co.uk). This story shows how real these risks are and how serious you should take them.

Approach

I’ll lead you through different concrete examples one-by-one to give you a feel for what I am talking about. Towards the end I’ll then try to extract the commonalities and derive a systematic approach for recognizing the involved risks plus some measures on how to mitigate them.

Direct transactions

Imagine a direct transaction, e.g. you go into a super market and buy an apple. You get the apple and the shopkeeper gets your money.

Even in these simple direct transactions there are risks involved, e.g. your apple may be rotten and you only notice later or your money may be counterfeit money. In this discussion I’ll not talk about those direct risks much more, but keep in mind that they always exist in addition to all the indirect risks, we’ll look at below.

Transactions involving legal titles

Let’s make this story a bit more indirect and let’s look at the same picture when you’re buying a house.

In the above picture time is flowing from left to right. On the left-hand side, the seller is registered in the land register as the owner of the house and the buyer is in possession of the funds. While this is not mandatory in many countries (in some countries it is) the transaction becomes safer (less risky) if an independent party (like a notary) also sets up an escrow account and the buyer transfers his funds first to this escrow account. The notary then takes care of the changes to the land register to make the buyer the new owner of the house and after the successful transfer of ownership rights via the land register he then transfers the funds from the escrow account to the seller.

The escrow account can be set-up with instructions for the bank in place so that money can only flow to either the buyer (in case that the transaction would need to be rolled-back) or the seller (in case the transaction goes forward as planned), but not to the notary. This set-up ensures that the notary cannot transfer the money to his own account.

We have several new elements here:

- Land register

- Notary

- Escrow account

- Right of possession / legal title

You have more indirection here in this example than in the shop example above as you cannot take real estate into your hand and walk away with it. You’re not exchanging the physical good any longer, but only a legal title. A legal title enables the holder of that title to use the machinery of rule-of-law (court, police, …) to enforce his rights. Countries have set-up land registers in order to make it transparent for everyone who needs to know who has which legal title in relationship to real estate. In addition, not everybody is allowed to make changes to that register, but there exist “gate-keepers” (like notaries) who oversee the correct handling of changes to the land register.

While in this example we already have more indirection, due to the fact that we don’t talk about the concrete physical thing any longer (like the apple in the first example) this scenario is still very transparent. After the transaction you can verify that you have all the prerequisites to enforce your rights in case you’d need to by getting an excerpt from the land register.

Just as a side remark: the above description is quite similar to the situation when you own a part of a “limited liability company” (Kapitalgesellschaft). This ownership has to be registered in a commercial register via a notary.

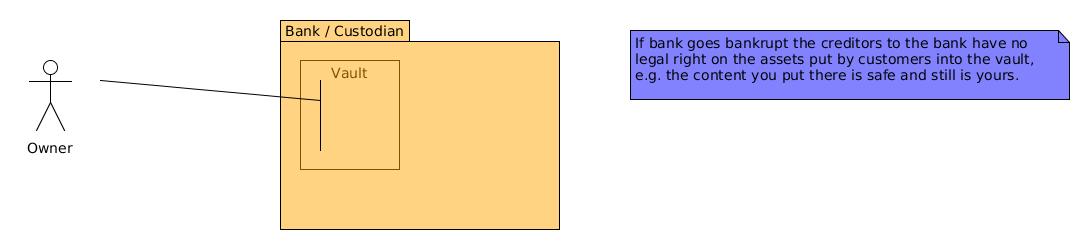

Bank as a custodian

Imagine a safe-deposit box in a bank.

The bank here acts as a service provider that most likely will charge you some fee for its service. The bank typically will not (need to) know what you put into the safe-deposit box. Maybe you put there some childhood pictures, or a birth certificate or cash. That’s up to you. The bank does not need to know. If the bank would go bankrupt the contents of the safe-deposit box are still yours and other creditors of the bank won’t have a claim on the contents. In this example we have again a few new elements:

- Service provider

- Undisclosed content

- (Insurance)

The situation is still quite transparent and you can check whenever you like that the contents of the box are as they should be. In addition, there may be an insurance involved that will pay you some money in case that the bank gets robbed and the contents of your box are stolen.

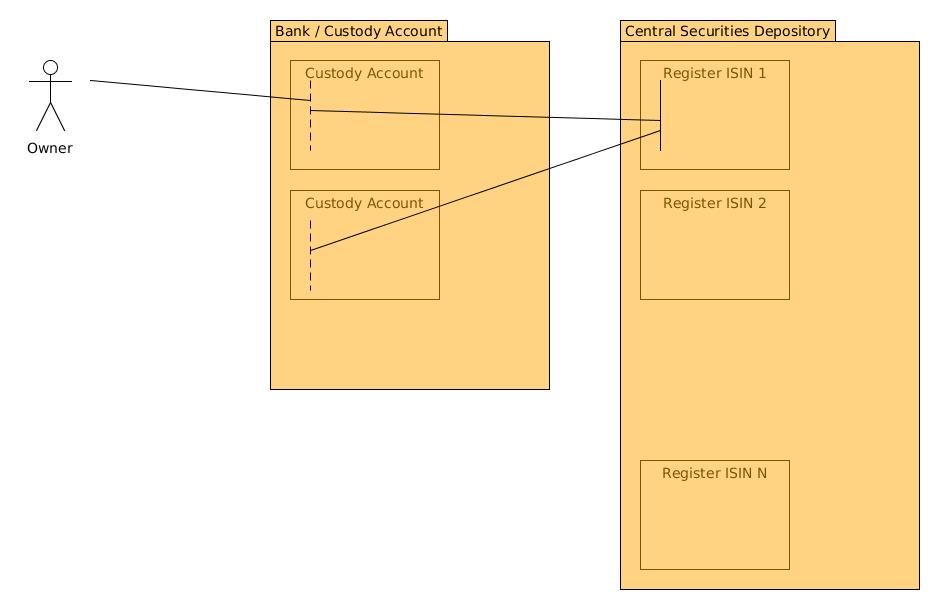

Bank with a custody account

Let’s look at the situation similar to the safe-deposit box, but concerning legal titles like securities. Imagine you have a custody account at a bank in which you have one share of ACME AG.

In the past shares were real pieces of paper and often your name was written on them (registered share) to make it more difficult for a thief to turn the legal title into money. This approach also made it more difficult to sell your shares to somebody else, because yours had to be destroyed and new ones in the new owner’s name had to be created.

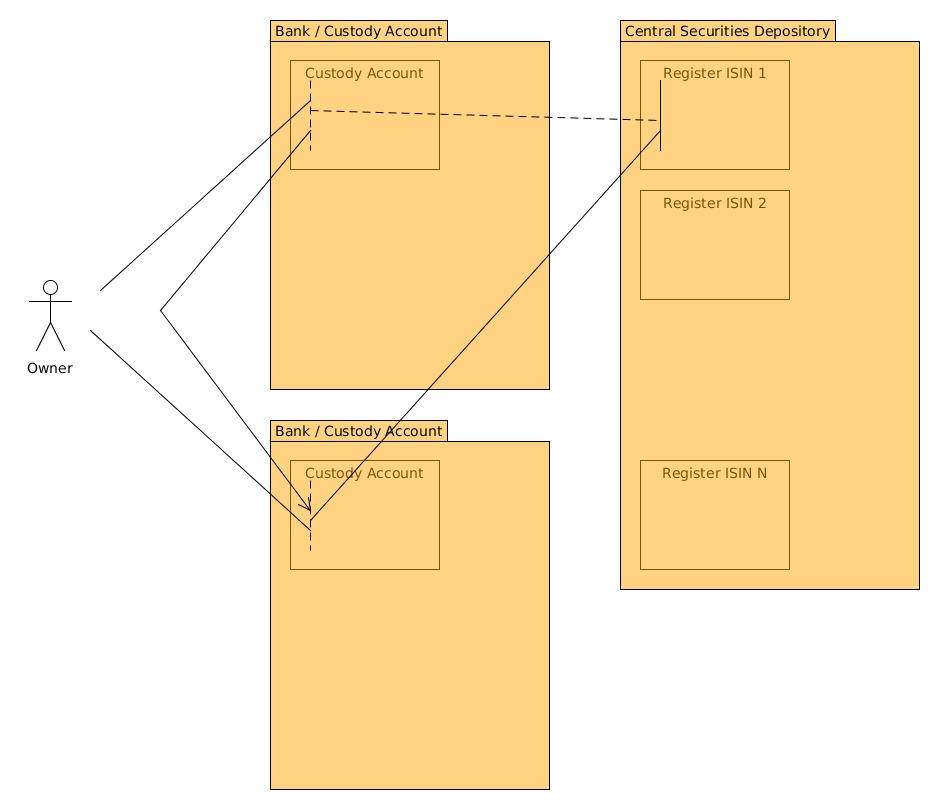

Nowadays there are special organizations called central securities depository (CDS) whose job it is to maintain registers of who owns how many securities of a given type (typically identified by something like an ISIN number or similar). These securities are fungible, meaning that one unit is indistinguishable from any other unit (imagine a liter of water; any other liter of water is as good as yours; liters of water are fungible). Most often you won’t have an own account at the central securities depository and only your custody account bank will have an account there. Your custody account bank will group all securities of the same type together into a so called omnibus account.

We have here some elements that we saw already earlier:

- (Neutral) register

- Service provider

- Legal title

And we have some new elements:

- Fungible goods

- Black box

- Omnibus account

If the custody account bank would go bankrupt your securities in your custody account are still yours like in the example with the safe-deposit box and other creditors of the bank won’t have a claim on your custody account contents.

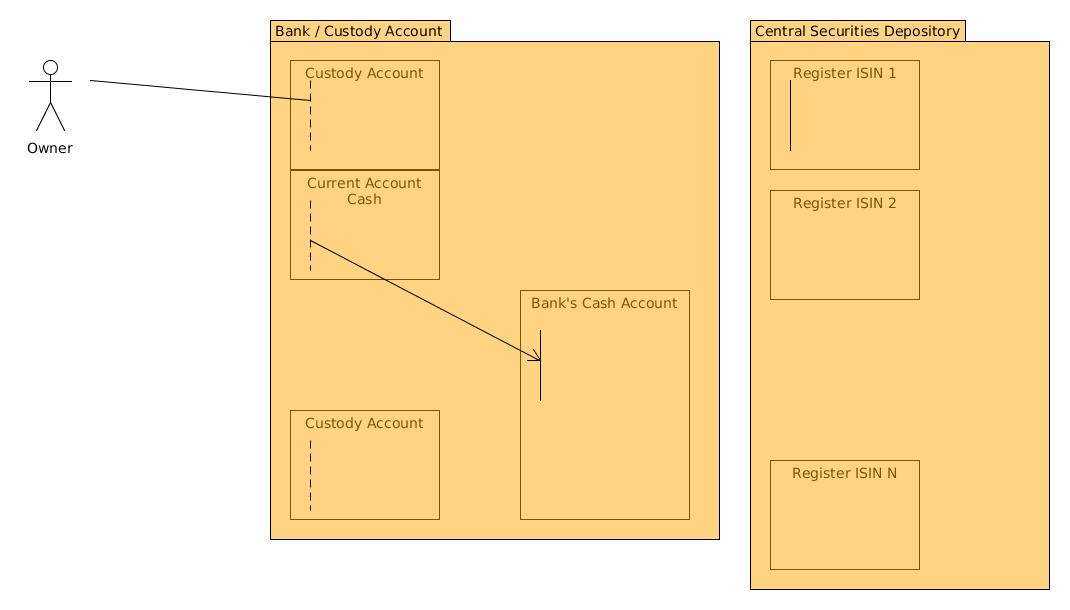

Here we have for the first time a real instance of indirection risk. Consider the following picture, which may be fraud or may be legally ok depending on which contract you have with your custody account bank (see further below):

Imagine you buy a share of ACME AG and pay for them with funds on your current account, but the bank does not actually buy the share on the market and only shows you on your account statement that you “have” that share. How would you know? Perhaps the bank expects that you’re really crappy at investment decisions and waits until you sell your share with a loss. Then you get the money corresponding to that sell price and the share disappears from your account statement. That share never existed in the first place.

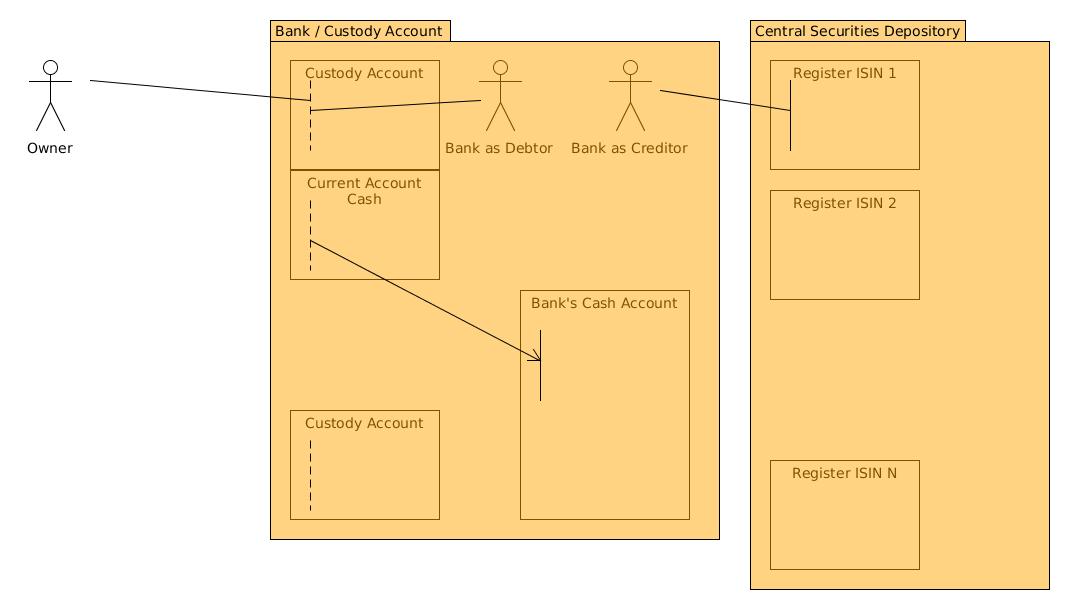

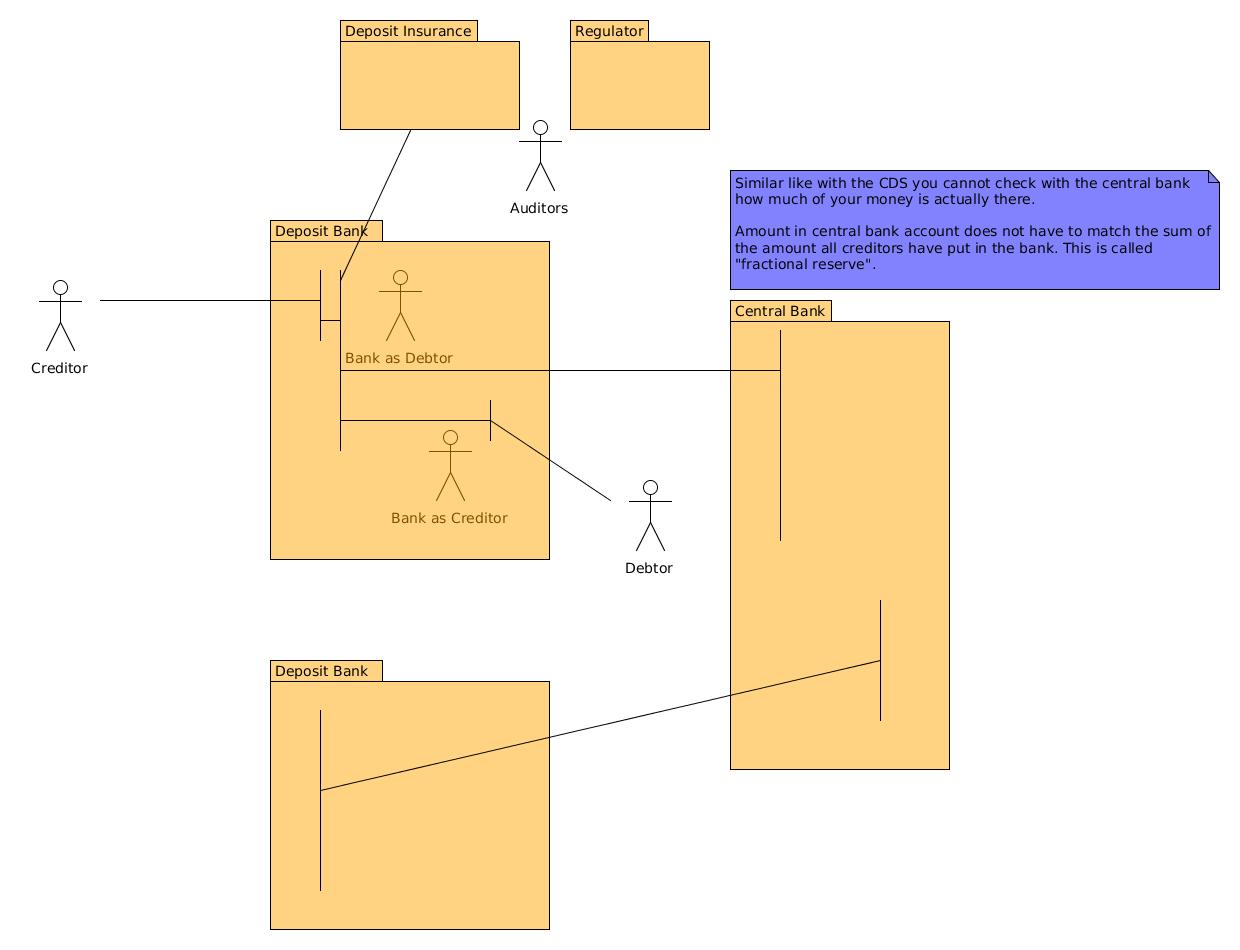

Bank as debtor

I said above that depending on your contract agreement with your custody account bank this behaviour may or may not be considered fraud. As an example, consider the Dutch online broker DeGiro that was recently acquired by flatex AG. It has (had) the account types standard and custody. If you chose the standard type then you allowed the broker to lend your shares to others. If DeGiro makes use of that right then the bank becomes a debtor to you and your account statement does not show the amount of shares you have, but only your claims against the bank for a given number of shares. Once you gave the bank the allowance to “lending to others”, this “lending to others” may also include lending to the bank itself. The bank can choose in how far it wants to hedge its positions in the market or not. The picture becomes essentially the following one:

The bank becomes a debtor to you and the bank is free to decide in how far it hedges its bets in the market. The bank is free to not hedge your purchase of the ACME AG share at all (like in the picture in the previous section).

But what happens if in this scenario the bank goes bankrupt? Then you’re basically out of luck and you have to wait in line with all the other creditors to the bank to see if and how much compensation you’re still able to get.

New elements:

- Counterparty risks

Options to verify the contents of the black-box

As said above: depending on your agreement with the bank the behaviour to only “act as if” you had the shares in your account might be fraud. How would you check?

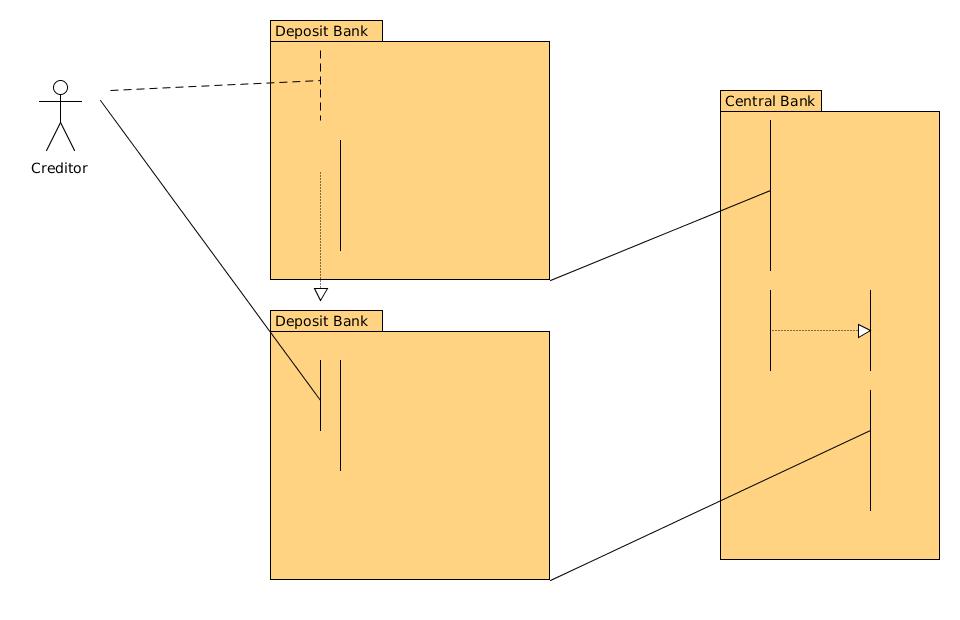

As you cannot check the underlying register like in our example with the land register what else can you do? The custody account bank is a black box, but it still exposes some “buttons” that you can press and see what happens outside the box. One option that comes to mind is that you open another custody account at another independent custody account bank and transfer your assets:

Your second custody account bank will also have an account at the central securities depository and at the time of the transfer your share in the first custody account bank has to really exist or otherwise the central securities depository will not credit the second custody account bank’s account with that share.

Bank deposits

Imagine you take 100€ to your bank and deposit them in your bank account. It took me quite some time to understand that the corresponding picture is not the one with the safe-deposit box, but the one with the DeGiro standard account type:

Once you deposit your 100€ with the bank you become a creditor to the bank and the bank becomes a debtor to you. Your account statement of your bank only tells you “I owe you 100€”. It does not say “I currently safeguard 100 of your €”. That’s relevant as we’ve seen above in case that the bank goes bankrupt, because then you have to wait in the line with all other creditors to the bank and see how much you still get.

The bank on the other hand lends your money to other people. In that relationship the bank is the creditor and the other person is the debtor. At that point is an “impedance mismatch”, typically between your short-term deposits and the other persons long term credit. In case that you and many others would need their money from your bank the bank cannot go to its debtors and ask them to give them their money, because the duration of the credits is typically many months or years (like for housing or similar).

The banking system looks like a hierarchical tree, where at the root there is the central bank playing a similar role as the central securities depository played in the securities example above. Banks typically will have an “omnibus account” with the central bank and use it to transfer money from one bank to another.

The banking system exists already for quite some time and people have come up with the concept of the central bank as lender of last resort in cases where a bank is in principle able to cover all the withdrawals, but “just not now” due to the above mentioned impedance mismatch (the details of how a bank can go bust are quite well described in Where Does Money Come From?; they also describe the differences between “solvency crises” and “liquidity crises”). In addition, the banking sector is strongly regulated, e.g. Basel III and the national financial regulatory authorities like BaFin in Germany. Furthermore there exist deposit insurances like the EU regulated deposit insurance for all banks in the EU. In Germany the deposit insurance goes even further with Bundesverband deutscher Banken BdB (for private banks, see also einlagensicherungsfonds.de), Bundesverband Öffentlicher Banken Deutschlands VÖB (for public sector banks), Bundesverband der Deutschen Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken BVR (for co-operative banks) and Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband DSGV (savings banks).

So even if you yourself cannot get transparency for what’s going on in the black box the auditors of the financial regulatory authorities and from the deposit insurances plus the reporting obligations under Basel III give you quite some comfort in the lawful operation of the banks and the banking system. In addition the insurances work somehow similar like the indorsements on commercial papers and its associated contract liabilities (in German: Garantiefunktion des (Voll-)Indossaments bei einem (Handels-)Wechsel), e.g. like a cascade of liable parties if one cannot pay the next one has to pay.

Elements we saw already earlier:

- (Neutral) register

- Service provider

- Legal title

- Fungible goods

- Black box

- Omnibus account

- Counterparty risks

New elements:

- (Deposit-)Insurance

- Regulation and regulatory authorities

- Auditors

- Transparency to regulatory authorities via mandatory regular reporting

Audits are in principle already an improvement compared to no audits, but personally I am always wary when the company that is audited is covering the costs of the auditor. This contradicts the principle of conflict of interest. Similarly, I do not trust the credit rating agencies very much as they’re also paid by the company to be audited.

The situation is already better with audits performed by a regulatory authority. In these cases there is at least their reputation at stake (the reputation of the regulatory authority).

I think the best set-up is when you have an insurance organization that has skin in the game in case that the insured party goes bankrupt and then audits the insured party. In such cases it is much more likely that these audits act as a safety measure against awry business practices. And as an additional benefit you have a two stage cascade for liabilities:

- in the first stage the bank is liable to you and

- in the second stage the insurance company is liable to you.

Associated to regulation like Basel III there are many reporting requirements that have to be fulfilled. These reporting requirements are not to you, but to independent government (or government near) organizations. These reporting requirements at least to some degree bring a bit of light into the black-box.

Options to verify the contents of the black-box

Just to mention it, also with a deposit bank you can use the transfer of money from one bank to another independent bank as a verification mechanism to see if “your money is really there”.

Funds

Funds are legally structured similarly like a “safe-deposit box”, e.g. even if the fund organization would go bankrupt your assets remain yours. In addition, funds must have a published rule-set that is meant to help and protect investors. It should help investors to judge the associated risk and it should protect investors from fund manager actions that you would not approve. This may be a plus, but it may also be a minus. Imagine in a crisis situation like COVID-19. If the rules of the fund say that the volume of shares invested in Italian companies has to be between 5% and 15% it prevents the fund manager from selling all its shares from Italian companies, even if it actually might be a benefit for the investors.

I am not sure how exactly the assets were managed in the Madoff investment scandal, but imagine they were managed via a fund. How do you know that the trades a fund is telling you were made are actually done? A fund is a black box and the reports you get are cheap pieces of paper or even cheaper web pages or PDFs. I don’t know how funds are supervised/regulated/audited, but do you know?

In principle it would be best if there would exist an independent public (government owned?) infrastructure that takes care of the “raw machinery” of buying and selling assets, managing accounts and issuing account statements. If then in addition funds would be required to operate on top of that infrastructure and allow their investors to get high level information about their activities directly from that infrastructure operator then you could gain a high level of confidence that the assets are actually there. Regulators could also get more detailed insight and perform their audits on top of that data from the raw machinery.

Another option to handle this risk would be if the investor would open a custody account at a bank of his choosing and give the fund operator the power to perform the required bookings in that account.

Again, another option would be if a third-party insurance company would be required to insure the value of the assets under management to have skin in the game and then have the right (and obligation) to audit the activities of the fund manager in detail.

In principle this is the same risk as above with DeGiro or other brokers in that you cannot be sure that there is no counterparty risk involved. In principle a fund is not meant to involve any counterparty risk of the fund manager and if it does it most likely would be considered fraud. But how can you verify and be sure?

ETFs

ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds) often are considered cheaper and equally well performing as managed funds. They track an index like Dow Jones or DAX, e.g. they not only calculate the index but buy and sell the underlying stocks in ways that will make the total value of the fund track as closely as possible the value of the calculated index.

Here are some indirection risks that are often overlooked like for example most new indices will not include the dividends. The DAX index is one of the few indices that include dividends. This may mean that the cheap management fees may actually not be that cheap (the fund operator earns all the dividends).

The other issue with ETFs is that they track an index. The index is calculated by an independent organization. This independent organization does not guarantee the error free calculation at all times and the damage this may cause. Imagine that the index calculating organization makes a mistake in their calculations on the day that you sell and the mistake is such that the value of the index is lower than what the correct value would be. What will happen then? What are ETF companies supposed to do? I actually don’t know what happens in such scenarios, but I also did not find any source of information that would explain in transparent and end-customer friendly language how ETF funds are supposed to handle such situations. Most likely that’s stuff that will be only explained in the fine print of every ETF.

Even if the index is calculated correctly there may be ways for third-parties to influence the index in ways that are bad for you. For example, have a look at the Libor scandal.

Elements we saw already earlier:

- Service provider

- Legal title

- Fungible goods

- Black box

- Omnibus account

- Counterparty risks

- Regulation and regulatory authorities

- Auditors

- Insurance

New elements:

- Index operator

- Index manipulation

- Insight/transparency via an independent booking infrastructure

Derivatives / structured products

Often people think about derivatives as something they would never want to deal with. They think about exotic financial instruments that only people in “high finance” would touch. But in recent years a lot of derivatives have been created that are attractive for the “normal street investor”, too. Like for example discount certificates, which may even help to lower the risk of investing.

It is important, though, to know that all these kinds of products come along with counterparty risk, because they’re contracts between you and the issuer. They don’t tell you anything about how the issuer hedges his own risks, e.g. if he actually performs underlying trades to hedge his risks or simply hopes that the market will move in a direction where you lose and the issuer wins.

Often your “house-bank” will try to sell you these kinds of derivatives, which are issued by the same parent company (of course they assure you that there are measures in place that ensure that there are no conflicts of interest). Even if the derivatves are not issued by the same bank that advises you the advisor may earn more commission with one issuer than with the other. What do you think which derivative they’ll offer to you? This is again a case where there is large potential for conflict of interest.

Another thing that makes me nervous is that it seems that these types of derivatives are still a good way for banks to earn money. Where do you think that money comes from? Via some path it will come out of your pocket.

Interest rate brokers

In Germany I know of (in alphabetical order):

- check24 (together with Sutor Bank and using in the back-end services from Deposit Solutions GmbH),

- Savedo (now part of Deposit Solutions GmbH),

- Weltsparen (Weltsparen is a brand of Raisin GmbH and it cooperates with the Raisin Bank AG) and

- Zinspilot (a brand of Deposit Solutions GmbH and in cooperation with Sutor Bank)

who act as interest rate brokers. They basically connect German customers with banks in the European Union so that German customers can deposit money at those banks for higher interest rates than German banks would offer.

Typically, there are 3 parties involved, the fintech company acting as agent/facilitator, the bank acting as payment/money transfer service provider and the target deposit bank where the money is finally deposited. Typically, the amount of money you can deposit at the target banks is restricted to 100’000€ so that in case of the bank going bust the European deposit insurance would ensure that the German customer would not lose any money.

You have to pay a bit of attention with banks in countries that do not use the Euro as currency (e.g. Poland, Croatia, … or similar), because in those countries the equivalent of 100’000€ are insured, but in home currency, e.g. in case of a bankruptcy you may get your money, but in home currency and you may end up with some currency risk.

From that perspective, so far, all looks fine. But now comes the but 😃

Several of the above companies will have a rather slim process for opening a bank account. Sometimes you even do not have to sign a piece of paper, you simply get a PDF explaining to you the conditions and with your transfer of money to the bank account number printed on the PDF you implicitly agree to those conditions and become a customer. Once the money was deposited at the target bank you get a PDF or other electronic statement in the web-interface of the agent/facilitator telling you that the money was deposited. What could possibly go wrong?

What would happen if a hacker would manage to get control over the web-site of the agent/facilitator? What if they print on the PDF that tells you where to transfer your money to their own account number? As the hacker is in control of the agent/facilitator web presence they’d then issue an electronic statement to you that gives you a false sense of security that your money actually was deposited in the target bank, but in fact it wasn’t. If you signed up for a longer-term deposit, let’s say a year or so, you may only notice after 12 months that your money is lost. Who would cover that risk? Even if the agent/facilitator would agree to cover this security risk, would they have deep-enough pockets, would they be solvent enough, to cover for a large-scale fraud affecting many customers, each one of them depositing several 10’000€?

The involved bank only agrees to take care of the proper money transfer and in the just described hacker scenario the money may never touch that bank, because you transferred your money to the hacker’s account. The bank was never involved. You made the mistake of trusting the info on the web-site or PDF!

Assuming a bit more criminal energy on the side of the interest rate broker you could also imagine that they just say that they have a cooperation with a bank ABC in country XYZ and ask you to transfer money to their own account. If you check you’ll see that the bank ABC exists and is really part of the European deposit insurance, so you’ll trust the offer. You transfer the money and receive the electronic statement in the web-interface of the interest rate broker giving you a false sense of security that your money was deposited. A year later you notice that your money never reached that bank and your money is gone with the founders or employees of the interest rate broker. In principle, to cover that risk you’d have to ask the target bank to confirm that they actually have a valid agreement with the interest rate broker before transferring your money.

In these interest rate broker businesses, the agent/facilitator is meant to take care of all customer requests, e.g. even if you deposit your money with the target bank the target bank has no capacity for handling German speaking customers. So even if you write to these target banks (either via e-mail or paper mail) to verify the “ground truth” they will try to redirect you to the agent/facilitator and refuse to communicate with you. You have to be really insistent until you actually get a valid response from them (I went through that process to see for myself what would happen; they only reacted to a registered paper mail (Einschreiben) and only because I was already a customer; e-mails were simply ignored).

As said above: In principle you’d have to ask the target bank to confirm that they actually have a valid agreement with the interest rate broker before transferring your money. But as the target banks are even reluctant to communicate with you even after you’re a customer they won’t even look at you and your request before you’re a customer. There are enough people out there who just transfer their money without doing their share of due-diligence.

In principle, the whole interest rate broker business could be handled without requiring trust in the intermediary:

- It is possible for the target banks to create legally binding eIDAS (electronic IDentification, Authentication and trust Services) electronically signed statements.

- The target banks could create an eIDAS signed statement confirming the cooperation with the interest rate broker published on the web-site of the interest rate broker. Ideally this document would already contain the IBAN number of the account you should transfer your money to. Like that the target bank confirms that the offer on the web-site of the interest rate broker is legitimate and they also tell you to which account number you should transfer the funds in case you want to participate in their offer.

- After the money was successfully deposited at the target bank the target bank could issue another eIDAS signed account statement confirming your deposit and published via the web-presence of the agent/facilitator.

Via that mechanism the interest rate brokers keep the target banks out of the communication chain and no trust is required in the interest rate broker or their security infrastructure. They only act as a facilitator who publishes legally binding electronically signed statements issued by the target banks. But currently no one of the interest rate brokers follows such a process.

Even if the above mentioned end-to-end electronic signature legally binding communication channels would be in place you still would need to verify the banks themselves, e.g. do they really exist (ideally via the register at the national deposit insurance of the target country; this look-up in the register at the national deposit insurance would at the same time tell you that your deposits are really insured) and ideally also check their solvency to some degree (ideally via independent credit ratings form the big rating firms; many banks won’t have that as these ratings have to be paid by the company to be rated).

All of that risk of potentially losing several tens of thousands of Euros of your hard-earned savings for that tiny interest rate advantage? That’s definitely not my cup of tea. In the absence of end-to-end legally binding electronic signatures the only other viable solution I’d see is that a solvent third party would insure and cover the full end-to-end process risk. See below.

Why are the above scenarios less of a problem in your standard banking business, e.g. in case you open a bank account with a pure internet bank? I guess one of the differences is that with other banks you have a slowly growing trust relationship starting only with little risk. You open up your bank account and transfer some money there. You then start to pay at restaurants or in shops with your credit card and see that all banking transactions are working fine. Slowly you may trust them more and give them bigger jobs to handle, e.g. your custody account or similar.

With these interest rate broker businesses you’re supposed to go “all-in” from the start without knowing them and without an effective way to verify if they really have a business relationship with the banks they say they have and without an effective way to verify that the money actually did arrive at the target bank. In addition, I would not think that they’re solvent enough to be able to cover the damage of a hacker or in-house employee fraud even if they wanted to.

The sparpiloten fraud

I already mentioned it at the very top: Only after developing this blog post and its systematic approach I found the story behind sparpiloten (the associated web-sites are offline by now: sparpiloten.ch/sparpiloten.co.uk). This story shows how real these risks are and how serious you should take them.

When I learned about the sparpiloten fraud their web-site was already offline and even via Wayback Machine I was not able to retrieve an older version of their web-site. I would have liked to see if there were visible indicators of the fraud on the surface already.

And remember: how do you know that check24, Savedo, Weltsparen or Zinspilot are not similar schemes?

Interest rate broker business inside a traditional bank

As already mentined above, in the absence of end-to-end legally binding electronic signatures in the interest rate broker businesses the only other viable solution I’d see is that a solvent third party would insure and cover the full end-to-end process risk.

The first larger German banks have started to replicate the interest rate broker business for their customers like Deutsche Bank or IKB or some Sparkassen. If the risks of the interest rate broker business model are covered by a solvent traditional bank, I’d say that the situation looks much better. You still would need to read the fine-print to find out which risks they actually cover, but if you go into the web-interface of your “house-bank” (the web-interface of your bank that you regularly use for any other bank businesses) and then click a button that says “transfer money to bank ABC in country XYZ” then I guess you can be quite sure that the bank is also liable for that action, that the bank ABC in country XYZ actually exists and is part of the European deposit insurance and that your money actually arrives there. You already trust your account statements of your “house-bank” and you have no more reason to mistrust the account statement telling you that your money deposit to the target bank was successful.

LIQID Cash

One other option I still have to look at is LIQID Cash. The offer is only available for the wider public since 2020-05-22 and therefore it is so new that I did not have the time to look into it in detail. But as far as I understand LIQID (the fintech facilitator) uses the infrastructure of Deutsche Bank Wealth Management for their transactions and LIQID only triggers these transactions. It will all depend on the details, but I could imagine that this can be done in a way without requiring trust in the fintech facilitator.

Elements we saw already earlier:

- Service provider

- Legal title

- Fungible goods

- Black box

- Counterparty risks

- Regulation and regulatory authorities

- Auditors

New elements:

- Accountability falling between chairs

- Nobody feels responsible for taking on that risk so that it remains with the customer, the person least in a position to adequately judge and handle that risk

- End-to-end process risk

- Clarification who carries that risk and

- Solvency of that party

- Man-in-the middle communication/process risk

- Fraud by hacker

- In-house employee fraud

Systematic approach

I hope that some of the above examples were able to convince you that the described risks are real and require your attention. I’ve tried to describe above the concept of “risk of indirection” by example. The whole purpose of these examples was to identify commonalities and then ideally come up with a systematic approach on how to think about these risks and ideally also an idea on how to treat/mitigate them.

Common elements:

- Typically, the core of the issue is that you’re dealing with something very abstract like a legal title rather than something very concrete like a bottle of water.

- Typically, there is a (financial) service provider involved that offers you services around these legal titles.

- Often these legal titles are in addition fungible goods, e.g. without individual identity.

- Often the service providers operate as a black box and you cannot see what’s happening inside.

- Closely related to this black box set-up is the fact that there is often a longer end-to-end process involved that you may not be fully aware of and/or that you may not fully understand.

- Sometimes there is not only one service provider involved, but several and it might not be fully clear to you who is accountable/liable for what. Some of the accountability may simply fall between chairs and in case of some damage you’re left in the rain.

- Sometimes unexpected counterparty risk may be involved, even in places where you did not think it is.

In the end the goal of managing those risks is to put you in a position in which you can be fairly certain that you can effectively enforce your legal title.

Check that the actors (named companies) actually exist via first principles, e.g. company registers or similar. Be in the (communication) driver seat! Initiate communication from your end and use different channels, ideally ones that will require real humans to think on their feet, e.g. asking questions on the phone and make sure that there are really knowledgeable people working. Perform your checks bottom up starting with the registers baked into the legal system like the commercial register. Get the last published balance sheet and the last audit report published in the company register. Try to get hold of credit ratings and find out if they’re part in some safety/protection schemes like a deposit insurance. If yes, then also perform the same checks with that insurance organization. If the companies involved have offices then potentially it might even make sense to visit them in their offices to get an idea of whom you’re dealing with. In one very recent case of a scam around windpark engergy it seems that the mentioned Holt Holding had their office at a gas station. Alone that could have raised a red flag to question their business model.

Transparency is king! Ideally that transparency includes the possibility for you to verify all transactions yourself. In cases where there are registers involved that are baked into the legal system like in the example above with the land register (Grundbuch) or the commercial register (Handelsregister) an ideal approach to managing these risks is to establish full transparency down into that register and set-up an escrow like transaction. This is most likely only working for non-fungible entities that possess an identity of their own. If you cannot get transparency yourself then try to find out if somebody else with skin in the game has a high level of transparency, e.g. auditors of insurers or regulatory authorities.

In most of our examples above the biggest risk comes from the fact that there is counterparty risk involved that you may not have expected. Suddenly there is counterparty risk with the service provider who was supposed to be just an intermediary. Ideally you avoid any additional counterparty risks from the intermediate service providers!

If possible circumvent the exposure to counterparty risk with this intermediat service provider all-together by implementing an end-to-end principle: in cases where you have to deal with fungible goods the real truth is still often recorded at an underlying register, but rather than accepting an omnibus account structure it would be best if you could get an individual account at that underlying register. Not necessarily in your name, but well separated from all other accounts, with its own unique ID and its own account statements that can be signed with a legally binding eIDAS electronic signature from the underlying register. Then you don’t have to trust the intermediate service provider but only the operator of the register recording the “final truth”, like a Central Securities Depository. This end-to-end electronic signature technique would also work in the example with the interest rate brokers above.

In cases where the end-to-end principle cannot be implemented the next step would be to identify (potential) counterparty risk in the end-to-end process. Sometimes you will find counterparty risk in places where you might not have expected it like with the DeGiro example above. If you identify counterparty risk you should manage it by first checking the solvency and credit rating of the counterparty and ideally have a second liable insurance party involved that will cover the damage in cases of default on the part of the primary counterparty. The insurer will have skin in the game and an innate interest to perform proper audits of the primary party.

Check for risks in the end-to-end process that are not covered by anyone like in the example above with the man-in-the-middle attack by a hacker or similar. If from the contract situation it is already clear that nobody except you is carrying the risk and you cannot do anything to minimize/eliminate that risk then you should not use the services offered by that service provider.

Even in cases where one of the involved parties agrees to be liable for some risk like the man-in-the-middle attack by a hacker you have to make sure that this party has deep enough pockets to actually be able to cover any damage if it were to happen (pay attention to Ltd/GmbH or similar company forms). Follow the same steps as for the counterparty risk above: perform research about the solvency and credit rating of the primary liable party and ideally try to have an insurer in the picture that then does the auditing to “encourage” the primary liable part to follow best practices throughout their work processes.

Regulation and audits from national financial regulatory authorities can help and can be considered a plus, but these audits will be so infrequent that this should definitely not be your only line of defence!

Sometimes the separation of concerns can help: sometimes you can reduce the overall risk if one party is responsible for deciding which actions to take and the other party is only responsible for the proper handling of those actions.

- As an example, consider an escrow account. The bank is making sure that money can only flow to the accounts of the buyer and seller. The neutral party (like a lawyer or a notary) can only trigger the payments. The neutral party cannot get the money to his own account.

- As another example consider the case of robo-advisors for asset management. The operator of the robo just says which actions to take, but the account is in the name of the customer with a bank that only performs the operations as given by the robo. The bank also ensures that only financial instruments can be traded that are agreed with the customer.

Sometimes the combination of accountability can help: sometimes you can reduce the overall risk if a financial potent party is embedding the end-to-end proces within its own organization and covering the end-to-end risk (like a bracket).

- As an example, consider the case described above where a bank like Deutsche Bank or IKB is offering the interest rate broker business as a full service out of one hand. If something goes wrong then the bank will be liable for any damage. The bank is already under a lot of scrutiny by the regulators and many protections are in place to prevent misconduct.

From time to time it might also be prudent to change your service provider and transfer your assets from one service provider to another. As explained above, these transfers are “moments of truth”, because the transfer will only work if the assets “really do exist”.

Outlook

Personally I am a bit disappointed by the national financial regulatory authorities like BaFin. I would have expected them to be more pro-active and stop financial service providers from operating if they do not implement the required safety measures like an end-to-end principle or an insurance. Why wait until the first black sheep rip off some customers before adapting the regulatory requirements? I’d wish that this topic attracts more interest and of a larger audience in order to push our financial regulatory authorities to become pro-active upfront before somebody gets hurt rather than applying their “laissez-faire” attitude and waiting until something goes wrong.

Real world examples:

Borderline: