Private Email with Mailu Behind Traefik Reverse Proxy

Published by Weisser Zwerg Blog on

Reclaim your privacy by running a self-hosted Mailu server on your home hardware, with a small virtual private server (VPS) and Traefik as the Internet-facing gateway.

Rationale

This post is part of the Digital Civil Rights and Privacy series. You’ll learn how to run your own Mailu e-mail system on a home server while using Traefik on a separate virtual private server (VPS) as a reverse proxy to serve as the gateway to the public internet. This design keeps all data at home under your physical control; the VPS only forwards traffic and stores nothing.

Two practical problems we’ll solve:

- The current guidance for using Traefik as a reverse proxy on a different host can be confusing or incomplete. This guide shows a clean, working setup.

- Many ISPs block outbound port 25, preventing direct delivery from a home connection. We’ll cover reliable workarounds using a VPS gateway.

I believe the most privacy-friendly setup is one you control: your server in your apartment, protected by you. With this approach you gain full data ownership while still being reachable on the public Internet via the VPS. We’ll also touch on deliverability essentials (DNS, authentication, TLS, reputation) and point to helpful resources for deeper reading.

Here are some helpful additional resources:

- Traefik as reverse proxy (different host)

- How to Setup a Mail Server on Debian Using Mailu and Start Sending Emails Today

- Building, deploying and securing your own mail server with Docker

- Self-hosted mail server: What you need today (c’t / heise+, Oct 20, 2023).

It explains the current bar for deliverability (DNS, auth, TLS, reputation) and why running your own server is getting tougher. - Home Server Blueprint: Rock-Solid Home Server with Unattended Reboots, Secure Disk Encryption, and Cost-Effective Offsite Backups

Different Readers and Different Levels of Prior Knowledge

Different readers have different levels of prior knowledge, so it is hard to write one guide that fits everyone. If the explanations below feel too short or too advanced for you, just copy the URL of this post into an AI assistant like ChatGPT and ask it to walk you through the sections you are not yet comfortable with. For example, you can ask it to explain unfamiliar concepts or show the same steps for a different Linux distribution.

Prerequisites

We will use Traefik as a Reverse Proxy on our netcup Virtual Private Server (VPS), which we set up earlier and made accessible over the internet.

In the Traefik docker-compose.yml from my previous post, I still use

traefik:v2.8.0. If you want to utilize a more recent version, check out Christian Lempa’s boilerplates and specifically his library/compose/traefik file. Currently, this usestraefik:v3.6.0.

For this guide, I’ll assume you’re working with a VPS, have Traefik set up as a reverse proxy on this VPS, and that the VPS is accessible via the internet.

Private Link: WireGuard (Networking and Network Topology Overview)

In order to connect the home host to the VPS you’ll need a private link: WireGuard/Tailscale/SSH-reverse or any other tunnel. We’ll use a WireGuard Hub-and-Spoke (Star) topology[1]. This setup allows us to securely access services like Mailu on your home server from anywhere on the public internet through the Traefik reverse proxy while keeping your data private and under your control.

Here’s a simple visual overview of the setup:

At the top of this configuration at the top of this Ʌ (upside-down V) is your VPS server reachable via the internet, which acts as the “hub” (“star-center”) and hosts the Traefik reverse proxy. Connected to this hub is your home server, where Mailu and other services will run. Both are linked securely using WireGuard in a Virtualized Mesh Network, creating a private and encrypted connection between them.

For a step-by-step guide on setting up a WireGuard virtualized mesh network, check out the WireGuard section in the ODROID-M1: Dockerized Home Assistant page.

Getting my Hub and Spoke setup to work took some time, mainly because I overlooked the following lines in the wg0.conf at my star center at my netcup VPS:

# Allow routing between clients

# PostUp = iptables -A FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -A FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT

# PostDown = iptables -D FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -D FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT

# The below rules are functionally equivalent to the simpler ones above but are "idempotent", e.g. can be run several times and still produce the same result

PostUp = iptables -C FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || iptables -A FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT; iptables -C FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || iptables -A FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT

PostDown = iptables -D FORWARD -i %i -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || true; iptables -D FORWARD -o %i -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || true

As detailed in Wireguard Netzwerk mit Routing einrichten.

Domain Name and DNS Service

To receive mail on your own server, you need a domain name such as example.com.

You purchase domains from a domain registrar and pay a yearly fee.

The price depends on the so-called top-level domain (TLD) - the part after the last dot.

For example, in example.com the TLD is .com.

Once you own a domain, choose a DNS provider for it. This might be the same company as your registrar, or a different one. Your DNS provider hosts your zone and publishes records (A/AAAA, MX, TXT, etc.) to the public internet. Most registrars let you change the domain’s nameservers to point at your DNS provider. After you switch nameservers, manage all your records at the DNS provider - not at the registrar.

I use Dynadot as the registrar and Cloudflare as the DNS provider. This combo supports DNSSEC and keeps things flexible. You can also keep both registration and DNS at Cloudflare, but I like separating roles.

DNSSEC has two steps: enable it at your DNS provider (which generates DS/keys) and publish the DS record at your registrar. Both sides must be configured for DNSSEC to be active.

Cloudflare doesn’t register every TLD. Availability changes over time, so check your desired TLD at both your registrar and Cloudflare rather than relying on specific examples that may be outdated.

For email-friendly TLDs with sensible pricing, consider .de, .name, .dev, .xyz, .pub, etc.

Note: you’ll publish MX records pointing to your Mailu hostnames (e.g.,

mail.example.com), but the e-mail addresses themselves may be under the root domain (e.g.,user@example.com).

Before moving on, pick a domain you want for mail (for example, your-last-name.name), register it, set up a DNS provider, and (ideally) enable DNSSEC.

Nice extras: enable WHOIS privacy at your registrar.

If you use Cloudflare, use DNS only (grey cloud) for any records used by mail so Traefik/Mailu handle TLS directly without Cloudflare in the middle.

Proxy status best-practice:

- DNS only (grey cloud) for

mail.example.com(SMTP/IMAP/POP3, submission, MTA-STS, etc.).- Proxied (orange cloud) is fine for pure web endpoints (e.g.,

webmail.example.com,autoconfig.example.com); set SSL/TLS mode → Full (strict) so Cloudflare validates your origin cert. ACMEdns-01validation works either way because it uses TXT records.

Cloudflare’s orange-cloud proxy does not proxy SMTP/IMAP/POP3.

Your MX must point to a grey-cloud (DNS-only) hostname, otherwise mail delivery will fail.

Keep mail.example.com grey; you may orange-cloud only web endpoints.

Set-Up

Mailu Setup Utility

Start with the Mailu setup utility.

It’s a simple web form. You fill in a few choices and download config files (including docker-compose.yml and mailu.env) to launch Mailu with Docker Compose on your home server.

My configuration follows the storage design from Home Server Blueprint: Rock-Solid Home Server with Unattended Reboots, Secure Disk Encryption, and Cost-Effective Offsite Backups.

I want my e-mail data encrypted at rest but excluded from nightly off-site backups, so I use the path /mnt/luks_btrfs_volume/@local_only_storage/mailu.

If you prefer your mail to be included in backups, use /opt/offsite_backup_storage/mailu instead.

As mentioned earlier, you’ll publish MX records pointing to your Mailu hostnames (e.g., mail.example.com), while the e-mail addresses can live at the root domain (e.g., user@example.com).

I personally keep addresses under the Mailu hostname (e.g., user@mail.example.com) to keep things explicit.

Autodiscovery tip: Many clients expect

autoconfig.<email-domain>(Thunderbird) andautodiscover.<email-domain>(Outlook).

- If your addresses are

user@example.com, publishautoconfig.example.comandautodiscover.example.com.- If your addresses are

user@mail.example.com, publishautoconfig.mail.example.comandautodiscover.mail.example.com.You can also add SRV records for Outlook if needed.

My setup utility choices (adapt to your network):

- Mailu storage path:

/mnt/luks_btrfs_volume/@local_only_storage/mailu - Main mail domain and server display name:

mail.example.com - Linked Website URL:

https://mail.example.com - Enable the admin UI:

yes - Enable the API:

no - Enable Web e-mail client:

snappymail - IPv4 listen address:

10.0.1.2; this is the IP of your home server in the WireGuard network. - Subnet of the docker network:

192.168.203.0/24; leave this as is. - Enable IPv6:

no - Enable an internal DNS resolver (unbound):

yes - Public hostnames:

mail.example.com,autoconfig.mail.example.com,autodiscover.mail.example.com

Once you’re done click on the Setup Mailu button at the bottom.

The web form does not accept

@characters in paths. Remove@while filling the form and add it back in the generated files afterward.

On the next page, the wizard shows direct download links. I install the stack under /opt/mailu:

> mkdir /opt/mailu

> wget https://setup.mailu.io/2024.06/file/347a00e2-eb92-46d1-b565-0bae0b8f1824/docker-compose.yml

> wget https://setup.mailu.io/2024.06/file/347a00e2-eb92-46d1-b565-0bae0b8f1824/mailu.envCheck both files before you start:

- Add back any

@you removed from the storage path indocker-compose.yml. - In my case the Linked Website URL didn’t propagate; set

WEBSITE=https://mail.example.cominmailu.env.

Because we’re behind a reverse proxy on a different host (the VPS), set the trusted proxy addresses (REAL_IP_FROM=):

- The IP that the VPS is known by in the internet, e.g.

1.2.3.4. This IP will be given to you by your VPS provider most likely in its online admin interface. - The IP that the VPS is known by in the WireGuard network, e.g.

10.0.1.1

So the parameter should read: REAL_IP_FROM=1.2.3.4,10.0.1.1

Also add the proxy protocol ports at the bottom of mailu.env:

PROXY_PROTOCOL=25,465,587,993,995,4190Now start the stack:

# The documentation says you should use: "docker compose -p mailu up -d",

# but as the docker-compose.yml file is in /opt/mailu the docker-compose project name is already mailu and you can omit the "-p mailu"

# In addition, for the first start I'd omit the -d so that you see the logs on the console.

docker compose upAnd then create the initial admin account (admin@mail.example.com; adjust the password) in a different console:

docker compose exec admin flask mailu admin admin mail.example.com PASSWORDNext we’ll adjust the Traefik reverse proxy on the VPS.

Traefik Reverse Proxy

The Mailu docs include Traefik as reverse proxy (different host). Use that as your baseline and then apply the adjustments below for a clean, working setup.

For a modern Traefik compose, I like Christian Lempa’s boilerplates and specifically his library/compose/traefik file. They track current v3.x conventions and are easy to adapt - check the image tag in the template you copy and pin the exact version you want to run.

Post-quantum (PQ) TLS in Traefik and clients: Traefik v3.5 added support for the hybrid key exchange X25519MLKEM768 (X25519 + ML-KEM-768) when built with Go 1.24+. On the client side, OpenSSL 3.5 started prioritizing hybrid PQ groups by default. You can probe a site with a recent OpenSSL:

openssl s_client -connect example.com:443 -tls1_3 -groups X25519MLKEM768.You can enable post-quantum key exchange in TLS (protects against harvest-now-decrypt-later) without changing certificates. In TLS 1.3 the thing that protects the session’s confidentiality (the key agreement) is decoupled from the thing that authenticates the server (its certificate/signature). That lets us swap in a post-quantum (PQ) key agreement - today, ML-KEM (Kyber) - while keeping your existing RSA/ECDSA certificates and new versions of Traefik since v3.5 support that.

Encrypted Client Hello (ECH): As of today, Traefik itself does not expose server-side ECH. The Go 1.24 standard library added ECH support for servers, so Traefik could adopt it in the future; follow the upstream issue for status.

Today, when you open a TLS connection, you whisper to the network “Hi, I’m going to host.name” (the Server Name Indication (SNI) inside ClientHello). Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) puts that whisper inside an encrypted envelope. On-path observers (ISP, café Wi-Fi, employer, national firewall) can still see the IP you reached, but not which exact hostname you’re visiting on that IP, nor a bunch of other client-fingerprinting details from the ClientHello.

Encrypted Client Hello hides the real SNI (hostname you’re asking for), ALPN choice, most of your ClientHello parameters (cipher suites, signature algorithms, supported groups, key shares, etc.). That cuts down passive hostname disclosure and TLS-fingerprinting.

It doesn’t hide the server IP, port, timing/size patterns, and any unencrypted DNS lookups you make to discover the site (unless you use DoH/DoT/ODoH). It also doesn’t hide the fact that you’re using ECH at all. But it prevents easy SNI blocking: many censors and enterprise boxes block by reading cleartext SNI; with ECH they must resort to cruder IP blocking.Why people care (practical wins): Privacy on shared infrastructure, if many domains live behind the same IP (CDN, large SaaS, shared hosting like a Traefik reverse proxy), ECH stops the network from learning which tenant/site you touched. Resistance to trivial censorship as “Block everything whose SNI matches example.com” no longer works; a censor has to block the whole IP range (collateral damage rises). Less client fingerprinting, since the real ClientHello is hidden, on-path trackers get less entropy to identify “this looks like Alice’s browser on her phone at lunch.”

Below is the configuration approach I use and why each choice matters:

http3: false (HTTP/3 (QUIC) vs. TLS‑passthrough): We’re implementing a TCP TLS‑passthrough router for mail.example.com on the port :443 that forwards HTTPS to Mailu’s front.

Some browsers (Brave, Edge) will try HTTP/3 over UDP/443 first.

Traefik handles HTTP/3 at the HTTP layer, not the TCP passthrough layer, so there’s no matching HTTP router for that host and as a consequence Traefik itself answers the H3 request with “404 page not found”.

Other browsers (Chrome/Firefox) are using HTTP/2 (TCP) and therefore hit the TCP passthrough, which works.

The reason, why Traefik behaves like that is that when HTTP/3 is enabled on an entrypoint, Traefik also opens UDP :443 and serves HTTP/3 itself; only HTTP routers (with TLS) can match H3 traffic.

Passthrough only applies to TCP/TLS, not to QUIC/UDP.

SMTP Port 25 and Server-First Protocols:

The SMTP port 25 example in the official Mailu docs (section Traefik as reverse proxy (different host)) needs extra care.

In the sample, mailu-smtp appears under services: but not under routers: - unlike other entries (for example, mailu-imaps) that show up in both places.

Simply adding a matching router is usually not enough for port 25.

Why? SMTP on port 25 is a server-first protocol: the client connects and then waits for the server’s greeting banner before sending anything.

Traefik’s TCP routing logic often relies on seeing client-first bytes (e.g., a TLS ClientHello for SNI matching).

With server-first traffic on 25/tcp, the client sends nothing initially, so Traefik has nothing to peek for SNI-based decisions and may never dial the backend.

In practice, two reliable options exist:

- Delegate port 25 to HAProxy: Use HAProxy instead of Traefik only for port 25. It handles server-first protocols well.

- Use a dedicated Traefik entrypoint for 25 with a single backend: If you insist on Traefik for 25, bind a separate entrypoint and attach one TCP router/service to it (no SNI multiplexing, no TLS on 25). This removes the need to inspect client bytes. For further details see How to handle Server First protocols?.

I tried the second solution with different versions of Traefik, but could not make it work. Therefore I reverted to use HAProxy for port 25 instead.

Restrict the Cloudflare API Token:

You’ll see a cf_api_token in the config.

This token lets your ACME client use the DNS-01 challenge to issue TLS certificates (e.g., via Let’s Encrypt).

Keep your existing

httpChallengeresolver for normal hostnames, and add a second resolver for Cloudflare/DNS-01.

Ideally, give this token only the rights it needs and scope it to a single zone. Create a custom API token in Cloudflare (preferred over the global API key) with:

- Zone → Zone → Read

- Zone → DNS → Edit

- Include only the zone

example.com. - Copy the token (we’ll use it as

CF_DNS_API_TOKEN, and you can also set the same value toCF_ZONE_API_TOKENfor best compatibility).

Use something along the lines of the following:

docker-compose.yml:

secrets:

cf_api_token:

file: ./secrets/cf_api_token

services:

traefik:

image: traefik:v3.5.3

command: --api.insecure=true --providers.docker

secrets:

- cf_api_token

environment:

CF_DNS_API_TOKEN_FILE: /run/secrets/cf_api_token

CF_ZONE_API_TOKEN_FILE: /run/secrets/cf_api_token

ports:

- "80:80"

- "443:443"

- "443:443/udp"

- "127.0.0.1:8081:8081"

# - "25:25" # handled via haproxy below to support "Server-first SMTP (banner first)";

# see https://doc.traefik.io/traefik/v3.0/routing/routers/ : How to handle Server First protocols?

- "465:465"

- "993:993"

- "995:995"

- "4190:4190"

volumes:

- /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock:rw

- ./traefik-config/traefik.yml:/etc/traefik/traefik.yml

- ./traefik-config/dynamic-mailu.yml:/etc/traefik/dynamic/dynamic-mailu.yml

- ./traefik-config/acme.json:/etc/traefik/acme/acme.json

haproxy25:

image: haproxy:3.2.7

container_name: haproxy25

restart: unless-stopped

ports:

- "25:25"

volumes:

- ./haproxy-config/haproxy.cfg:/usr/local/etc/haproxy/haproxy.cfg:rotraefik.yml:

global:

sendAnonymousUsage: false

log:

level: DEBUG

# experimental: # http3: true

entryPoints:

web:

address: ":80"

allowACMEByPass: true

http:

redirections:

entryPoint:

to: web-secure

scheme: https

# Make the redirect router *less* dominant than your ACME router:

priority: 1

web-secure:

address: ":443"

http2:

maxConcurrentStreams: 250

http3: false

# advertisedPort: 443

traefik:

address: ":8081"

# mailu-smtp:

# address: :25

mailu-imaps:

address: :993

mailu-pop3s:

address: :995

mailu-submissions:

address: :465

mailu-sieve:

address: :4190

providers:

file:

directory: /etc/traefik/dynamic

# filename: dynamic.yml

watch: true

docker:

exposedByDefault: false

watch: true

api:

insecure: true

certificatesResolvers:

default:

acme:

email: user@example.com

storage: /etc/traefik/acme/acme.json

httpChallenge:

entryPoint: web

cf-dns: # new dns-01 resolver for Cloudflare

acme:

email: user@example.com

storage: /etc/traefik/acme/acme.json

dnsChallenge:

provider: cloudflare

# Optional but handy:

delayBeforeCheck: 0

resolvers:

- "1.1.1.1:53"

- "8.8.8.8:53"

alpn:

acme:

email: user@example.com

storage: /etc/traefik/acme/acme.json

tlsChallenge: {} # TLS-ALPN-01 over :443dynamic-mailu.yml:

http:

routers:

mailu-acme-only:

entryPoints: [web]

# host-scoped ACME path -> only mail.example.com goes to Mailu

rule: "PathPrefix(`/.well-known/acme-challenge/`) && (Host(`mail.example.com`) || Host(`autoconfig.mail.example.com`) || Host(`autodiscover.mail.example.com`))"

service: mailu-web

priority: 1000

# (optional) Plain HTTP for mail host if you want Mailu to answer on :80

mailu-http:

entryPoints: [web]

rule: "Host(`mail.example.com`)"

service: mailu-web

priority: 50

services:

mailu-web:

loadBalancer:

servers:

- url: "http://10.0.1.2:80"

tcp:

routers:

mailu-websecure:

entryPoints: [web-secure]

# Add extra mail FQDNs here if you use them

rule: "HostSNI(`mail.example.com`) || HostSNI(`autoconfig.mail.example.com`) || HostSNI(`autodiscover.mail.example.com`) || HostSNI(`mta-sts.mail.example.com`)"

tls:

passthrough: true

service: mailu-websecure

# mailu-smtp:

# entryPoints: [mailu-smtp]

# rule: "HostSNI(`*`)"

# service: mailu-smtp

mailu-submissions:

entryPoints: [mailu-submissions]

rule: "HostSNI(`*`)"

tls:

passthrough: true

service: mailu-submissions

mailu-imaps:

entryPoints: [mailu-imaps]

rule: "HostSNI(`*`)"

tls:

passthrough: true

service: mailu-imaps

mailu-pop3s:

entryPoints: [mailu-pop3s]

rule: "HostSNI(`*`)"

tls:

passthrough: true

service: mailu-pop3s

mailu-sieve:

entryPoints: [mailu-sieve]

rule: "HostSNI(`*`)"

service: mailu-sieve

# https://doc.traefik.io/traefik/migrate/v3/#v352

# https://doc.traefik.io/traefik/reference/routing-configuration/tcp/serverstransport/

# serversTransports:

# ppv2:

# proxyProtocol:

# version: 2

services:

mailu-websecure:

loadBalancer:

proxyProtocol: {version: 2}

# serversTransport: ppv2

servers:

- address: "10.0.1.2:443"

# mailu-smtp:

# loadBalancer:

# proxyProtocol: {version: 2}

# # serversTransport: ppv2

# servers:

# - address: "10.0.1.2:25"

mailu-submissions:

loadBalancer:

proxyProtocol: {version: 2}

# serversTransport: ppv2

servers:

- address: "10.0.1.2:465"

mailu-imaps:

loadBalancer:

proxyProtocol: {version: 2}

# serversTransport: ppv2

servers:

- address: "10.0.1.2:993"

mailu-pop3s:

loadBalancer:

proxyProtocol: {version: 2}

# serversTransport: ppv2

servers:

- address: "10.0.1.2:995"

mailu-sieve:

loadBalancer:

proxyProtocol: {version: 2}

# serversTransport: ppv2

servers:

- address: "10.0.1.2:4190"haproxy.cfg:

global

# log to stdout (supported in 3.2)

log stdout format raw local0

master-worker

defaults

mode tcp

log global

option tcplog

timeout connect 5s

timeout client 2m

timeout server 2m

frontend smtp_in

bind :25

default_backend mailu_smtp

backend mailu_smtp

# PROXY v2 toward Mailu so it sees real client IPs

server mailu 10.0.1.2:25 send-proxy-v2 check inter 5s rise 2 fall 2Reverse DNS for the VPS Public IP

Set the reverse DNS (PTR) of your VPS’s public IP to mail.example.com.

This is a key signal for mail deliverability and helps receivers trust your server.

I set this in my VPS control panel under the rDNS (Reverse DNS / PTR) section.

What “good” looks like (forward-confirmed rDNS):

- PTR:

IP → mail.example.com(set at your VPS provider; you can’t set PTR in your own zone). - A/AAAA:

mail.example.com → IP(set in your DNS provider). - HELO/EHLO: Your SMTP banner should present

mail.example.com.

These three should agree. Many receivers check for this “forward-confirmed reverse DNS” and penalize mismatches.

The PTR must be set on the IP that sends outbound mail. In this design, that’s the VPS (your public gateway), not the home server.

Quick tests

# Reverse lookup (should return mail.example.com)

dig +short -x 1.2.3.4

# Forward lookup (should return your VPS IP)

dig +short mail.example.com A

dig +short mail.example.com AAAA

# SMTP banner (look for EHLO and hostname)

nc -vz mail.example.com 25 || telnet mail.example.com 25Egress for SMTP Port 25

My home Internet Service Provider (ISP) blocks outgoing traffic (egress) on SMTP port 25, which is the standard port for server-to-server e-mail delivery. This means that any service running on your home network - including your Mailu server - cannot open direct SMTP connections to other mail servers on the internet. This is often called a “port 25 block” or “SMTP egress filtering”.

ISPs do this to prevent spam and abuse: infected home machines are often used to send large volumes of unsolicited e-mail directly to other mail servers, and blocking port 25 stops that. Instead, they expect customers to send mail via authenticated submission ports (like 465 or 587) on a trusted mail provider, where abuse controls and rate limits can be enforced.

Because we also want our Mailu system to send e-mail to the outside world, we need to find a workaround for this port 25 block.

Smarthost/Relay

The simplest workaround is to use a smarthost (relay) and send all outbound mail through a provider on port 587 (STARTTLS) or 465 (implicit TLS) with authentication. A smarthost is basically another mail server that accepts your outgoing messages and then delivers them to the final destination on your behalf. From the point of view of the internet, mail appears to come from the smarthost, not from your home server.

Mailu natively supports RELAYHOST, RELAYUSER, RELAYPASSWORD, and OUTBOUND_TLS_LEVEL.

When you use a relay, the OUTBOUND_TLS_LEVEL value encrypt is recommended.

Example providers include Amazon SES, Postmark, SendGrid (Twilio), SMTP2GO, Mailgun, and others.

While this option is the simplest, I advise against it because it defeats the whole purpose of keeping all data at home under our physical control. Once you use a smarthost or relay, all your outgoing e-mail passes through a third party, and even if you use end-to-end encryption, the metadata - who you talk to, how often, and how much you send - is still visible to them.

Therefore, I recommend keeping direct delivery and egress via the VPS, using policy routing and NAT. The goal is to route only TCP port 25 traffic from Mailu to the VPS over WireGuard and then perform SNAT (Source Network Address Translation) on the VPS. In practice, this means only your SMTP server-to-server traffic (port 25) leaves your home via the encrypted WireGuard tunnel to the VPS. The VPS rewrites the source IP (SNAT) so that other mail servers on the internet see the VPS’s public IP as the sender, while all mailbox data and state remain on your home server.

Source Network Address Translation (SNAT) and Policy Routing

SNAT (Source Network Address Translation) means rewriting the source IP (and optionally the source port) of packets as they leave a system.

On Linux this is done with iptables in the nat table, specifically in the POSTROUTING chain, which is consulted just before packets leave an interface.

There you use targets like SNAT (with a fixed --to-source 1.2.3.4) or MASQUERADE (which automatically uses the interface’s current IP) to change the source address.

The kernel’s conntrack (connection tracking) subsystem then keeps a state table that maps each connection’s original 5-tuple (internal IP/port, external IP/port, protocol) to its translated version,

so that replies coming back to the public IP can be “untranslated” and delivered to the correct internal host.

This whole SNAT process makes it look to both sides as if they were talking directly, even though the traffic is actually traversing a NAT gateway.

Modern systems often use iptables-nft, which keeps the familiar iptables command line and semantics but programs rules into the newer nftables engine under the hood;

the concepts of nat/POSTROUTING/SNAT/conntrack stay the same, only the backend implementation changes.

Below I will show you two scripts, one for the home server (smtp-egress-home-via-vps.sh) and one for the VPS (smtp-egress-vps.sh), that implement SNAT and policy routing for this narrow use case.

With smtp-egress-home-via-vps.sh and smtp-egress-vps.sh we build a very narrow SMTP egress path via WireGuard and a VPS.

The home script marks only TCP/25 flows from the Mailu Docker subnet, uses a separate policy routing table to send those marked packets through the WireGuard interface, and installs firewall rules that allow this traffic out while accepting only the corresponding replies. The VPS script then forwards these packets to the internet and applies SNAT so that they appear to come from the VPS’s public IP with a matching PTR record and EHLO hostname, effectively bypassing the ISP’s port-25 block while leaving all non-SMTP traffic from the home network completely unchanged.

In other words:

- At home you decide “only Mailu’s SMTP traffic goes through the tunnel,” and everything else continues to use your normal internet connection.

- On the VPS that SMTP traffic leaves with a clean, static public IP that you control in DNS, which is important for mail deliverability and reputation.

Pitfalls

The most difficult part of getting this working was adding the raw-table exception (see the smtp-egress-home-via-vps.sh script below) that allows SMTP replies from the WireGuard interface wg0 to reach the containers and that must run before Docker’s raw-table drop rules.

The raw table runs before conntrack and long before the filter table chains (including DOCKER-USER and FORWARD).

Docker installs per-container “hairpin guard”[2] rules that drop any packet destined for a container IP if it did not enter via that container’s bridge interface.

Because our reply traffic arrives on wg0 (not from the Docker bridge), it gets dropped in the raw table’s PREROUTING chain and never reaches the DOCKER-USER accept rules (see the script below).

In other words, Docker assumes that packets for a container should always arrive through the corresponding bridge. Anything that appears “from the outside” directly on another interface looks suspicious and is dropped early in the raw table to prevent hairpin and spoofing issues.

Debugging this was tricky, because iptables -vnL DOCKER-USER counters stay at 0 for the br-8288… DROP rule: the packets never reach the filter/DOCKER-USER chain at all - they die earlier in the raw table.

I was able to get a trace by:

# $CIP is the container's IP (must be 192.168.203.x) iptables -t raw -I PREROUTING 1 -i wg0 -p tcp --sport 25 -d "$CIP" -j TRACE nft monitor trace iptables -t raw -D PREROUTING -i wg0 -p tcp --sport 25 -d "$CIP" -j TRACEAnother hurdle was that nft’s live tracer (because I am on iptables-nft) does not log much to the traditional kernel log on iptables-nft systems. The old way to look at traces was:

dmesg -w | grep TRACEBut on iptables-nft systems nothing shows up there; instead you have to use

nft monitor traceto see the trace output.

WireGuard Config Nuance

You also need to adapt the WireGuard configuration on both the home server and the VPS.

On the Home Server

On the home server, you should set AllowedIPs = 0.0.0.0/0 on the home-to-VPS peer and Table = off in the [Interface] section.

In WireGuard, AllowedIPs is both a routing selector and an access control list.

By using 0.0.0.0/0 on the peer that points to the VPS, you tell the kernel: “any IPv4 destination is allowed to go through this tunnel if the routing policy sends it there.”

Without this, only the prefixes (for example only traffic originating from 10.0.1.2) listed in AllowedIPs would be eligible to use the tunnel.

We then set Table = off and use policy routing so that we do not hijack all traffic.

By default, wg-quick adds routes for each AllowedIPs entry into your main routing table.

If you set AllowedIPs = 0.0.0.0/0 and keep the defaults, wg-quick will install a default route via wg0, and your entire internet traffic will go through the VPS (which is not what we want here).

Setting Table = off (again, in the [Interface] section) on the home server tells wg-quick not to add any routes at all.

This way, only the packets we explicitly mark (with fwmark 25) are policy-routed into table 100 and forwarded via wg0.

All other traffic continues to use the normal default route of your home internet connection.

On the VPS Side

On the receiving VPS side, you need to add AllowedIPs = 192.168.203.0/24, 10.0.1.2/32 to the peer that represents your home server.

On the VPS, AllowedIPs in the home-peer entry plays the “reverse” role: it defines which source addresses are allowed to arrive from that peer, and which destination addresses the VPS is allowed to send back through that tunnel.

Because the Mailu containers at home use 192.168.203.0/24 as their source addresses, the home-to-VPS tunnel must permit that subnet.

You also include the home node’s WireGuard tunnel address (10.0.1.2/32) so that return traffic to the peer itself works cleanly.

In practice, this means the VPS will accept packets coming from 192.168.203.0/24 over the tunnel and knows that replies to those addresses (and to 10.0.1.2) should be sent back via the WireGuard peer, not via its normal default gateway.

Configurations and Scripts

You can find the relevant fragments below.

wg0.conf on the home server:

# sudo systemctl restart wg-quick@wg0 # after editing wg0.conf (Table=off etc.)

# sudo /usr/local/sbin/smtp-egress-home-via-vps.sh enable

[Interface]

Address = 10.0.1.2

PrivateKey = xxx

# IMPORTANT: we control routing with policy rules. Prevent wg-quick from injecting routes automatically.

Table = off

# Keep overlay reachability to the 10.0.1.0/24 WG network (hub on VPS).

PostUp = ip route add 10.0.1.0/24 dev wg0 || true

PostDown = ip route del 10.0.1.0/24 dev wg0 || true

# Optional but recommended (avoid drops with policy-routing asymmetry):

PreUp = sysctl -w net.ipv4.conf.all.rp_filter=2

PostDown = sysctl -w net.ipv4.conf.all.rp_filter=0

[Peer]

PublicKey = yyyy

Endpoint = vps.example.net:51820

# CRITICAL: this allows WireGuard to accept/encapsulate traffic to ANY Internet dest via this peer.

AllowedIPs = 0.0.0.0/0, 10.0.1.0/24

PersistentKeepalive = 25wg0.conf on the VPS server:

# sudo systemctl restart wg-quick@wg0 # after editing wg0.conf

[Peer]

PublicKey = zzz

# IMPORTANT: include Mailu's container subnet so replies to 192.168.203.0/24 go back over wg0.

AllowedIPs = 10.0.1.2/32, 192.168.203.0/24smtp-egress-home-via-vps.sh

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -Eeuo pipefail

# --------- adjustable ---------

WG_IF="wg0"

MAILU_NET="192.168.203.0/24" # Docker Mailu subnet

MARK_HEX="0x19" # 0x19 == 25 (smtp)

TABLE="100"

PRIO="10025"

# --------------------------------

ipt() { iptables -w "$@"; }

iptn() { iptables -w -t nat "$@"; }

iptm() { iptables -w -t mangle "$@"; }

iptr() { iptables -w -t raw "$@"; }

sys() { sysctl -q "$@"; }

save_sys() { sysctl -n "$1" 2>/dev/null; }

restore_sys() {

local key="$1" file="$2"

[ -f "$file" ] || return 0

# Strip whitespace/newlines; expect a bare value like "0|1|2"

local val; val="$(tr -d ' \t\r\n' < "$file")"

[ -n "$val" ] && sys -w "$key=$val" || true

}

STATE_DIR="/run/smtp-egress-home"

mkdir -p "$STATE_DIR"

case "${1:-}" in

enable)

# Record and set sysctls we rely on

save_sys net.ipv4.ip_forward >"$STATE_DIR/ip_forward.prev" || true

save_sys net.ipv4.conf.all.rp_filter >"$STATE_DIR/rpf_all.prev" || true

save_sys net.ipv4.conf."$WG_IF".rp_filter >"$STATE_DIR/rpf_wg.prev" || true

save_sys net.ipv4.conf.default.rp_filter >"$STATE_DIR/rpf_def.prev" || true

sys -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1 >/dev/null || true

sys -w net.ipv4.conf.all.rp_filter=2 >/dev/null || true

sys -w net.ipv4.conf.default.rp_filter=2 >/dev/null || true

sys -w net.ipv4.conf."$WG_IF".rp_filter=2 >/dev/null || true

# Try to detect the Docker bridge for MAILU_NET (works well for /24 like 192.168.203.0/24).

NET_PREFIX="${MAILU_NET%/*}" # e.g. 192.168.203.0

PREFIX3="${NET_PREFIX%.*}." # e.g. 192.168.203.

BR_IF="$(ip -o -4 addr show | awk -v pfx="$PREFIX3" '$2 ~ /^br-/ && index($4,pfx)==1 {print $2; exit}')" || BR_IF=""

[ -n "$BR_IF" ] && save_sys "net.ipv4.conf.$BR_IF.rp_filter" >"$STATE_DIR/rpf_br.prev" || true

[ -n "$BR_IF" ] && sys -w "net.ipv4.conf.$BR_IF.rp_filter=2" >/dev/null || true

# Allow container SMTP towards wg0 and allow return traffic

ipt -C DOCKER-USER -s "$MAILU_NET" -o "$WG_IF" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || ipt -I DOCKER-USER 1 -s "$MAILU_NET" -o "$WG_IF" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT

# Accept replies from wg0 to the Mailu subnet *before* Docker's DOCKER/bridge hairpin drop.

ipt -C DOCKER-USER -i "$WG_IF" -d "$MAILU_NET" -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || ipt -I DOCKER-USER 1 -i "$WG_IF" -d "$MAILU_NET" -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT

# Raw-table exception: let SMTP replies from wg0 reach containers (must run *before* Docker's raw drops)

iptr -C PREROUTING -i "$WG_IF" -d "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --sport 25 -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || iptr -I PREROUTING 1 -i "$WG_IF" -d "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --sport 25 -j ACCEPT

# MARK ONLY tcp/25 from Mailu subnet

iptm -C PREROUTING -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j MARK --set-mark "$MARK_HEX" 2>/dev/null || iptm -A PREROUTING -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j MARK --set-mark "$MARK_HEX"

# Policy rule: fwmark -> table 100

ip rule show | grep -q "fwmark $((0x19)).*lookup $TABLE" || ip rule add fwmark "$MARK_HEX" table "$TABLE" pref "$PRIO"

# Table 100: default via wg0 (device route)

ip route show table "$TABLE" | grep -q "^default" || ip route add default dev "$WG_IF" table "$TABLE"

# NAT bypass on wg0 for exactly this flow (top of chain)

iptn -C POSTROUTING -o "$WG_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || iptn -I POSTROUTING 1 -o "$WG_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT

echo "Enabled: SMTP-only egress via ${WG_IF} (fwmark=${MARK_HEX} -> table ${TABLE})."

;;

disable)

iptn -D POSTROUTING -o "$WG_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || true

iptr -D PREROUTING -i "$WG_IF" -d "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --sport 25 -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || true

ipt -D DOCKER-USER -s "$MAILU_NET" -o "$WG_IF" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || true

ipt -D DOCKER-USER -i "$WG_IF" -d "$MAILU_NET" -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || true

iptm -D PREROUTING -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j MARK --set-mark "$MARK_HEX" 2>/dev/null || true

ip rule del fwmark "$MARK_HEX" table "$TABLE" pref "$PRIO" 2>/dev/null || true

ip route flush table "$TABLE" 2>/dev/null || true

# Restore sysctls (if recorded)

restore_sys net.ipv4.ip_forward "$STATE_DIR/ip_forward.prev"

restore_sys net.ipv4.conf.all.rp_filter "$STATE_DIR/rpf_all.prev"

restore_sys net.ipv4.conf.default.rp_filter "$STATE_DIR/rpf_def.prev"

# Recompute BR_IF (best-effort) to restore its rp_filter if we changed it

NET_PREFIX="${MAILU_NET%/*}"; PREFIX3="${NET_PREFIX%.*}."

BR_IF="$(ip -o -4 addr show | awk -v pfx="$PREFIX3" '$2 ~ /^br-/ && index($4,pfx)==1 {print $2; exit}')" || BR_IF=""

[ -e "/proc/sys/net/ipv4/conf/$WG_IF/rp_filter" ] && restore_sys "net.ipv4.conf.$WG_IF.rp_filter" "$STATE_DIR/rpf_wg.prev" || true

[ -n "$BR_IF" ] && [ -e "/proc/sys/net/ipv4/conf/$BR_IF/rp_filter" ] && restore_sys "net.ipv4.conf.$BR_IF.rp_filter" "$STATE_DIR/rpf_br.prev" || true

echo "Disabled: SMTP-only egress via ${WG_IF}."

;;

status)

echo "=== ip rule ==="; ip rule

echo "=== table $TABLE ==="; ip route show table "$TABLE"

echo "=== mangle PREROUTING (tcp/25 mark) ==="; iptables -t mangle -S PREROUTING | grep -- "--dport 25" || true

echo "=== nat POSTROUTING (${WG_IF} tcp/25 bypass) ==="; iptables -t nat -S POSTROUTING | grep -E "${WG_IF}|ACCEPT|MASQUERADE" || true

echo "=== DOCKER-USER rules (active) ==="; iptables -S DOCKER-USER | grep -E "${WG_IF}|${MAILU_NET}|dport 25|ESTABLISHED" || true

echo "=== sysctls ==="; echo -n "ip_forward="; sysctl -n net.ipv4.ip_forward

echo "=== DOCKER-USER (counters) ==="; iptables -vnL DOCKER-USER || true

echo "=== raw PREROUTING (${WG_IF} -> ${MAILU_NET} tcp sport 25) ==="; iptr -vnL PREROUTING | grep -E "${WG_IF}|${MAILU_NET//\//\\/}|sport 25" || true

;;

verify)

set +e

echo "=== Preflight ==="

ip -br link show dev "$WG_IF"

echo "Peer selection requires: WG peer AllowedIPs include 0.0.0.0/0"

echo

echo "Policy lookup without mark (should use main table):"

ip route get 8.8.8.8 || true

echo

echo "Policy lookup WITH mark $MARK_HEX (should resolve via ${WG_IF} in table ${TABLE}):"

ip route get 8.8.8.8 mark "$MARK_HEX" 2>/dev/null || echo "(could not verify; check peer AllowedIPs and table $TABLE)"

echo

echo "Counters:"

iptables -t mangle -vnL PREROUTING | grep -E "dpt:25|MARK" || true

iptables -t nat -vnL POSTROUTING | grep -E "${WG_IF}|ACCEPT|MASQUERADE" || true

iptables -t raw -vnL PREROUTING | grep -E "${WG_IF}|${MAILU_NET//\//\\/}|sport 25" || true

;;

*)

echo "Usage: $0 {enable|disable|status|verify}"

exit 1

;;

esacDedicated smtp-egress.service on the home server (waits for wg0 + Mailu network):

# /etc/systemd/system/smtp-egress.service

# systemctl daemon-reload

# systemctl enable --now smtp-egress.service

[Unit]

Description=SMTP egress policy routing (Mailu -> VPS via wg0)

Wants=wg-quick@wg0.service docker.service

After=wg-quick@wg0.service docker.service

# If you have a systemd unit for Mailu, add it here:

# Wants=mailu.service

# After=mailu.service

[Service]

Type=oneshot

RemainAfterExit=yes

# Wait for wg0

ExecStartPre=/usr/bin/bash -lc 'until ip link show wg0 >/dev/null 2>&1; do sleep 1; done'

# Wait for Docker to have installed its chains (DOCKER-USER is what the script touches)

ExecStartPre=/usr/bin/bash -lc 'until iptables -S DOCKER-USER >/dev/null 2>&1; do sleep 1; done'

# Wait for the Mailu bridge interface that owns 192.168.203.0/24 to exist (matches the script’s autodetect logic)

ExecStartPre=/usr/bin/bash -lc 'until ip -o -4 addr show | grep -qE '\'' br-[^ ]+ +inet 192\.168\.203\.'\''; do sleep 1; done'

ExecStart=/usr/local/sbin/smtp-egress-home-via-vps.sh enable

ExecStop=/usr/local/sbin/smtp-egress-home-via-vps.sh disable

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.targetsmtp-egress-vps.sh

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -Eeuo pipefail

# ====== adjustable ======

WAN_IF="eth0"

WG_IF="wg0"

MAILU_NET="192.168.203.0/24"

PUB_IP="1.2.3.4" # VPS public IPv4 with correct PTR/rDNS

# ========================

ipt() { iptables -w "$@"; }

iptn() { iptables -w -t nat "$@"; }

iptm() { iptables -w -t mangle "$@"; }

sys() { sysctl -q "$@"; }

case "${1:-}" in

enable)

sys -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1 >/dev/null || true

# Allow ONLY Mailu-subnet SMTP from wg0 out to the Internet, and allow return.

ipt -C FORWARD -i "$WG_IF" -o "$WAN_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || ipt -A FORWARD -i "$WG_IF" -o "$WAN_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT

ipt -C FORWARD -i "$WAN_IF" -o "$WG_IF" -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || ipt -A FORWARD -i "$WAN_IF" -o "$WG_IF" -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT

# PMTU safety through the tunnel

iptm -C FORWARD -i "$WG_IF" -p tcp --tcp-flags SYN,RST SYN -j TCPMSS --clamp-mss-to-pmtu 2>/dev/null || iptm -A FORWARD -i "$WG_IF" -p tcp --tcp-flags SYN,RST SYN -j TCPMSS --clamp-mss-to-pmtu

iptm -C FORWARD -o "$WG_IF" -p tcp --tcp-flags SYN,RST SYN -j TCPMSS --clamp-mss-to-pmtu 2>/dev/null || iptm -A FORWARD -o "$WG_IF" -p tcp --tcp-flags SYN,RST SYN -j TCPMSS --clamp-mss-to-pmtu

# Explicit SNAT for ONLY tcp/25 from the Mailu subnet. Insert at top to outrank generic MASQUERADE.

iptn -C POSTROUTING -o "$WAN_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j SNAT --to-source "$PUB_IP" 2>/dev/null || iptn -I POSTROUTING 1 -o "$WAN_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j SNAT --to-source "$PUB_IP"

echo "Enabled: SMTP egress via ${PUB_IP} (only tcp/25 from ${MAILU_NET})."

;;

disable)

iptn -D POSTROUTING -o "$WAN_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j SNAT --to-source "$PUB_IP" 2>/dev/null || true

iptm -D FORWARD -i "$WG_IF" -p tcp --tcp-flags SYN,RST SYN -j TCPMSS --clamp-mss-to-pmtu 2>/dev/null || true

iptm -D FORWARD -o "$WG_IF" -p tcp --tcp-flags SYN,RST SYN -j TCPMSS --clamp-mss-to-pmtu 2>/dev/null || true

ipt -D FORWARD -i "$WAN_IF" -o "$WG_IF" -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || true

ipt -D FORWARD -i "$WG_IF" -o "$WAN_IF" -s "$MAILU_NET" -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT 2>/dev/null || true

echo "Disabled: SMTP egress via ${PUB_IP}."

;;

status)

echo "=== Interfaces ==="; ip -br addr show dev "$WAN_IF"; ip -br addr show dev "$WG_IF"

echo "=== IP forward ==="; sysctl -n net.ipv4.ip_forward

echo "=== FORWARD (counters) ==="; iptables -vnL FORWARD

echo "=== NAT POSTROUTING (counters) ==="; iptables -t nat -vnL POSTROUTING

echo "=== MANGLE FORWARD (MSS clamp) ==="; iptables -t mangle -vnL FORWARD | grep -i mss || true

;;

verify)

set +e

echo "=== Preflight ==="

ip -br link show dev "$WG_IF"

ip -br link show dev "$WAN_IF"

echo "Check that wg peer AllowedIPs include 192.168.203.0/24 so return to Mailu goes over wg0."

echo

echo "=== Rule presence ==="

iptables -S FORWARD | grep -E "$WG_IF|$WAN_IF|dport 25" || true

iptables -t nat -S POSTROUTING | grep -E "SNAT --to-source $PUB_IP|$MAILU_NET|dport 25" || true

echo

echo "=== Hints to actively validate in another terminal ==="

echo "VPS WAN side (should show src $PUB_IP): sudo tcpdump -ni $WAN_IF 'tcp port 25 and src $PUB_IP'"

echo "VPS WG side (should show src 192.168.203.x): sudo tcpdump -ni $WG_IF 'tcp port 25 and src net $MAILU_NET'"

echo "Conntrack view: sudo conntrack -L -p tcp --dport 25 | grep -E 'src=|dst='"

;;

*)

echo "Usage: $0 {enable|disable|status|verify}"

exit 1

;;

esacDedicated smtp-egress-vps.service on the VPS server:

# /etc/systemd/system/smtp-egress-vps.service

# systemctl daemon-reload

# systemctl enable --now smtp-egress-vps.service

[Unit]

Description=VPS SMTP egress gateway (SNAT tcp/25 from Mailu subnet via wg0)

Wants=wg-quick@wg0.service network-online.target

After=wg-quick@wg0.service network-online.target

# If you use a firewall manager that applies rules late, add it here so we run after it:

# After=ufw.service nftables.service

# When wg-quick@wg0 stops, also stop this (so ExecStop runs and cleans up)

PartOf=wg-quick@wg0.service

[Service]

Type=oneshot

RemainAfterExit=yes

# Wait for interfaces to exist

ExecStartPre=/usr/bin/bash -lc 'until ip link show wg0 >/dev/null 2>&1; do sleep 1; done'

ExecStartPre=/usr/bin/bash -lc 'until ip link show eth0 >/dev/null 2>&1; do sleep 1; done'

# Optional but strongly recommended: ensure the public IP is actually configured on WAN_IF

# Replace 1.2.3.4 and eth0 to match your script variables.

ExecStartPre=/usr/bin/bash -lc 'until ip -o -4 addr show dev eth0 | grep -q " 1.2.3.4/"; do sleep 1; done'

ExecStart=/usr/local/sbin/smtp-egress-vps.sh enable

ExecStop=/usr/local/sbin/smtp-egress-vps.sh disable

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

WantedBy=wg-quick@wg0.serviceConfigure Mailu via the Admin Web Interface

At this point, you’ve set up all the required infrastructure, so from here on you can mostly follow standard setup guides such as:

- How to Setup a Mail Server on Debian Using Mailu and Start Sending Emails Today

- Building, deploying and securing your own mail server with Docker

Log in to the Mailu admin interface as your admin@mail.example.com user with the password that we set earlier via the docker compose exec command, using one of the hostnames of your mail system, for example mail.example.com.

Right after the first login, change this password to a strong one. You can also choose the “Update password” option in the left menu.

The admin account is the “root” of your mail system. If someone gets this password, they can reset user passwords, read mail and change DNS-related settings, so treat it like the keys to your whole setup.

DNS Entries for E-Mail

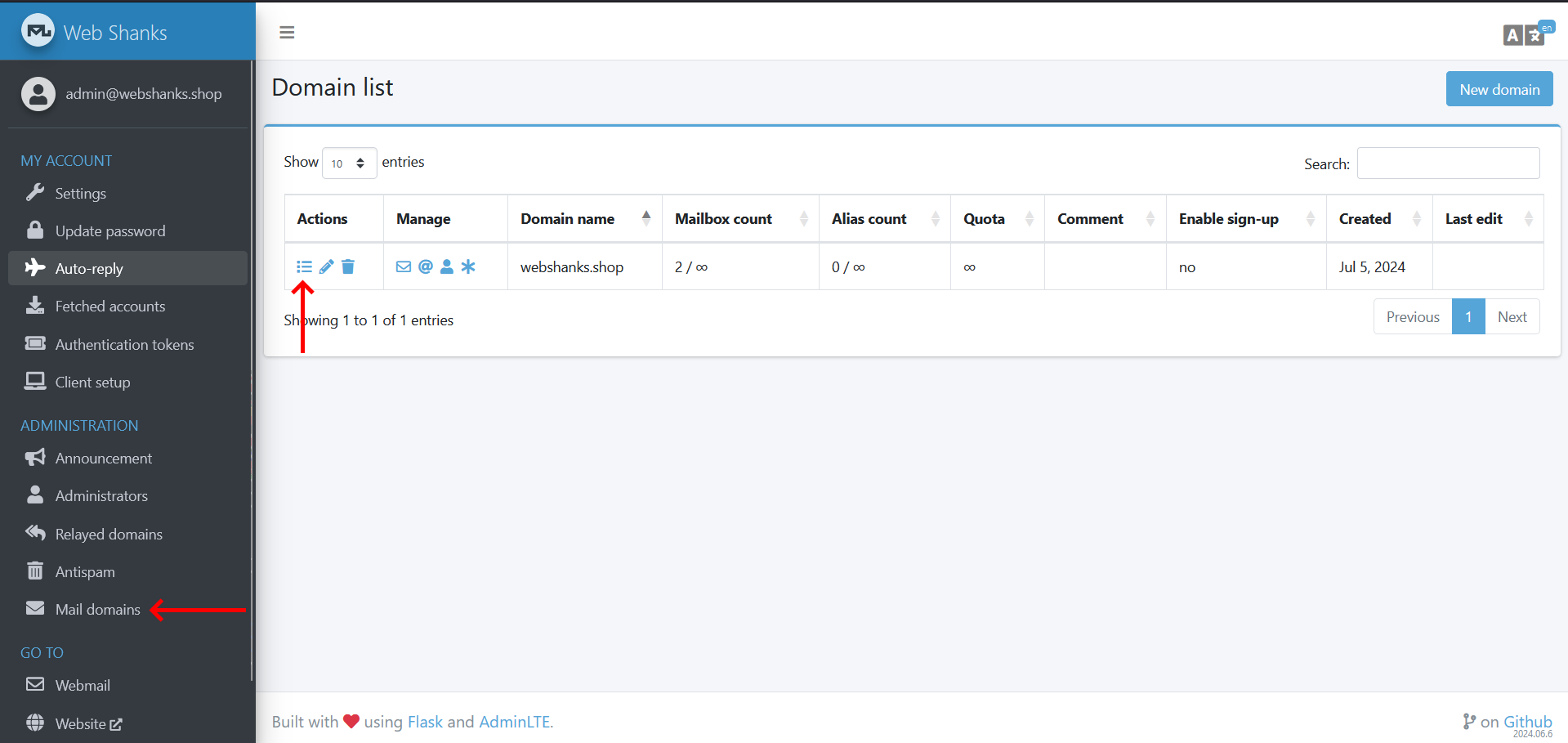

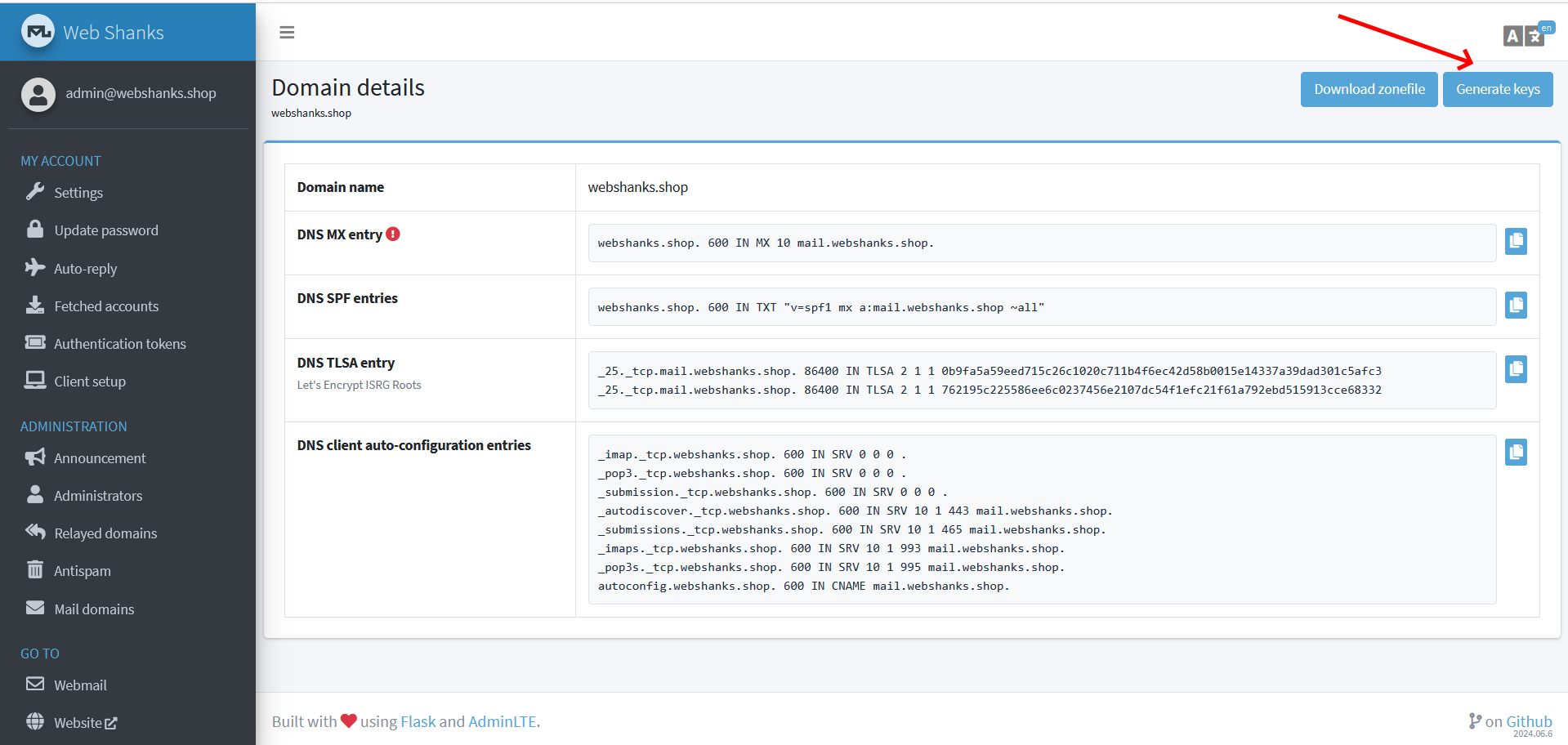

In the left menu, go to “Mail domains”, then in the table row for your domain, click the “Details” icon in the “Actions” column (the list icon with three horizontal lines). I am describing this in so much detail because it took me quite some time to find it.

On the domain details page, you can generate the keys that you will need for DKIM and DMARC.

- DKIM (DomainKeys Identified Mail) adds a cryptographic signature to your outgoing e-mail. Receiving servers can verify this signature using the public key you publish in DNS. This is a strong signal that the message really comes from your server.

- DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance) tells other mail providers how to handle messages that fail SPF/DKIM checks (for example, reject, quarantine, or just report). Even a basic “none” policy with reporting helps you see if someone is abusing your domain.

You will also need SPF (Sender Policy Framework), usually a single TXT record like

v=spf1 mx -all, which tells other servers which hosts are allowed to send mail for your domain. Together, SPF, DKIM and DMARC form the basic “authentication trio” most big providers expect today.

At the top right of the “Domain details” page, you can use the Download zonefile button. Download this file and import it at your DNS provider (for example, Cloudflare).

IMPORTANT: Before you import the zonefile from Mailu at your DNS provider, export the current state as a zonefile (or backup) from your DNS provider.

Some DNS providers may not accept the zone file “as is” but it still helps as a checklist: you can copy the individual records (A, AAAA, MX, TXT, etc.) into your provider’s web interface. Make sure you adjust the TTLs and any provider-specific flags if needed.

If your DNS provider supports DNSSEC, it is a good idea to enable it once your records are stable. Combined with DANE/TLSA, this can further improve the security of your mail transport, but it is an advanced step and not required for a working setup.

Once the DNS records are created and have propagated, you should see the “DNS MX entry” icon in Mailu turn into a green checkmark.

DNS changes are not instant. Depending on TTL and the provider, propagation can take from a few minutes to several hours. If you do not see the green checkmark yet, wait a bit and try again.

E-Mail Users

Next, you can create users on your mail system.

Again in the “Mail domains” section, click on the mail envelope symbol in the “Manage” column for your domain.

On the resulting page, you will find an Add user button at the top right. Use it to create all the user accounts you want at this point, for example user@mail.example.com.

You can always return to this page later to add or remove users.

E-Mail Aliases

It is also a good idea to set up e-mail aliases for some standard addresses such as:

abuse@mail.example.comhostmaster@mail.example.comnoc@mail.example.compostmaster@mail.example.comsecurity@mail.example.comwebmaster@mail.example.com

You can create these aliases by clicking on the @ symbol in the “Mail domains” section in the “Manage” column.

Many big providers and some anti-abuse systems expect domains to have working

abuse@andpostmaster@addresses. You can simply forward these aliases to your main admin inbox so you do not have to check multiple accounts.

Testing

At this point your mail system should be ready to go. To verify that everything is in good shape, you should perform a couple of tests.

Self-Mail Test in the Snappy Webmail Interface

Log out of the Admin Web Interface and log in to the Snappy Webmail interface by browsing to mail.example.com.

Use your newly created e-mail user’s username and password, then click Sign in Webmail.

As a first step, check that you can send an e-mail to yourself.

If that works: congratulations!

If that does not work, check the logs where you executed docker compose up to start your Mailu stack and look for errors. From there, fix the first error you see and try again.

Check SSL/TLS Certificates

You can perform both checks on the VPS where Traefik is running on.

# Check the SSL/TLS certificate for the IMAP connection at the Traefik level

> openssl s_client -connect mail.example.com:993 -servername mail.example.com -crlf -quiet

# Check the SSL/TLS certificate for the SMTPS (SMTP over implicit TLS/SSL) connection at the Traefik level

> openssl s_client -connect mail.example.com:465 -servername mail.example.com -crlf -quietWith openssl s_client you should see:

- The certificate chain (look for

subject=andissuer=lines). SSL-Sessioninformation showing a modern protocol (for exampleTLSv1.3).- A line like

Verify return code: 0 (ok)if everything is valid.

If verification fails, double-check your Traefik configuration (cert resolver, domains, SNI).

Configure Mail Client KMail

Next, configure a mail client like KMail or Thunderbird. Use parameters like the following:

- IMAP Server:

mail.example.com - Encryption: SSL/TLS

- Port: 993

- Username:

user@mail.example.com - Password: your credentials.

- Outgoing mail server (SMTP):

mail.example.com - Encryption: SSL/TLS

- Port: 465

- Username:

user@mail.example.com - Password: your credentials.

Some clients try “auto configuration” and may suggest different ports or non-encrypted connections. Always double-check that:

- IMAP uses port 993 with SSL/TLS.

- SMTP uses port 465 with SSL/TLS (implicit TLS), or 587 with STARTTLS if you configured it that way.

Once the client is connected, you should see your test e-mail from the previous webmail test in your inbox.

Now send another test e-mail to yourself using your newly configured mail client. If it shows up in webmail and in the client, your basic send/receive path is working.

Receiving External E-Mail

Next, check if your mail server is reachable by other mail servers via the public internet.

As port 25 is often blocked by ISPs on home networks, you need to run this test from a second VPS that can connect to port 25 on your mail server mail.example.com.

The following command tests basic connectivity:

> telnet mail.example.com 25If this does not work (for example, it hangs or cannot connect), then most likely port 25 is blocked by the internet provider.

You can also check that your mail server responds correctly using the swaks (Swiss Army Knife for SMTP) tool:

> swaks --server mail.example.com --port 25 --timeout 60 --quit-after HELOIf that works, you should be able to receive e-mails from the outside.

Verify this by using another e-mail account (for example, on a different provider) and sending a test message to user@mail.example.com.

If the test e-mail does not arrive:

- Check the sending provider’s bounce message (if any).

- Look at the SMTP logs in Mailu (

docker compose logs -f smtp). - Confirm that your DNS MX record points to

mail.example.comand not to an old hostname.

Sanity Checks

Finally, run some sanity checks on your mail system:

- SMTP Diagnostics: enter your mail server address, for example

mail.example.com. - Open Relay Test: enter your mail server address, for example

mail.example.com. - Domain Score (DMARC Score, SPF Score): enter your domain name, for example

example.com. - Test the Spammyness of your Emails: follow the on-screen instructions and send an e-mail to the address they give you.

- If you activated TLSA, you can use this free tool to validate your configuration: DANE/TLSA validator for inbound SMTP services.

Pay special attention to:

- Open relay: this must be closed. An open relay will quickly get your server blacklisted.

- SPF, DKIM, DMARC: these should all pass for messages you send to test services. They strongly influence deliverability.

- Reverse DNS (PTR record): your IP should resolve back to a hostname that matches (or is consistent with) your mail server’s identity.

Congratulations! At this point, you should have finished setting up your own e-mail server and confirmed that it works correctly.

Conclusions

In this guide, you’ve learned how to set up your own Mailu e-mail server behind traefik as a reverse proxy, with a small VPS in front and your main server safely running at home.

By hosting your own instance, you keep full control over your messages, metadata, and configuration instead of relying on a large provider.

You now have:

- A Mailu stack running on your home server.

- Traefik on a VPS acting as the internet-facing entry point.

- DNS, TLS, and basic deliverability checks in place.

- A setup that is private by design: the VPS only forwards encrypted traffic, while your data stays at home.

Running your own mail server is not “set and forget”, but with this architecture you have a strong, privacy-respecting base that you fully own.

Appendix

E-Mail Encryption (S/MIME, Autocrypt-PGP, WKD-PGP)

With the Mailu setup you built in this guide, you are already in a good position for privacy, especially if you run Mailu only for yourself at home and mainly communicate with other people who do the same. As long as your devices stay uncompromised, your messages are only accessible to you and your communication partners, with only limited metadata visible. From the outside world, only the connections between mail transfer agents (MTA-to-MTA) are visible. From that perspective, end-to-end encryption might look optional.

In normal e-mail, some metadata is always visible to the servers that relay your messages: sender, recipient, subject line, dates, and the servers that handled the message. The body may be protected in transit with TLS, but it is usually stored in clear text on each mail server unless you add end-to-end encryption.

So when does encryption add real benefits? It helps a lot when you communicate with people who use mail services run by other people or organizations (for example, big webmail providers or company servers). It is also useful if you worry that your home server could be compromised in the future. In these situations, end-to-end e-mail encryption makes sure that the message content (not the metadata) can only be decrypted on the endpoints (desktop PCs or mobile devices) when the recipient actually reads it.

Also, if you want to open up your Mailu installation on your home server for family and friends, encryption is a good idea. It means that, even as the server administrator, you technically cannot read the content of their e-mails, even if you wanted to.

All the work we do in this chapter of the appendix will also prepare us for the next chapter, where we will talk about Delta Chat, a decentralized and secure messenger app that uses e-mail and encryption as its backend. With the recently released Delta Chat Version 2, chats are end-to-end encrypted, always and by default. But more about that in the next chapter.

For your full understanding of the limitations of e-mail encryption more broadly here are a few good online write-ups that discuss the subject-line and other metadata limitations:

- Email Security on Privacy Guides: explains that metadata (including Subject) remains visible even when the body is encrypted.

- Email Encryption Options: SMTP TLS vs PGP vs S/MIME vs Portal Pickup on LuxSci blog: states clearly that PGP does not encrypt headers (sender, recipient, subject) and outlines implications.

- 15 reasons not to start using PGP on SecuShare: enumerates many practical limitations of PGP/e-mail and includes the subject-line / header metadata issue.

E-Mail Encryption Options

Currently, three main techniques are used for end-to-end e-mail encryption: S/MIME, Autocrypt-PGP, and WKD-PGP.

S/MIME’s big advantage over Autocrypt/WKD-PGP is how identity and trust are handled and how well it integrates with “normal” mail clients (especially corporate Outlook / Apple Mail setups). For a single private user, that can be useful if you talk a lot with people in more formal or enterprise environments. Otherwise, Autocrypt/WKD is usually simpler and at least as private for everyday use.

- S/MIME: Uses X.509 certificates issued by a certificate authority (CA). Trust is hierarchical: your mail client trusts certain CAs in its root store, and a CA vouches that this public key belongs to this e-mail address (and maybe name/organisation).

- Autocrypt: A convenience layer on top of OpenPGP. Your mail client automatically attaches your OpenPGP public key in a header and learns your peers’ keys from their headers. It intentionally does almost no key verification (opportunistic security), focusing on making encryption “just happen” between normal users.

- WKD (Web Key Directory): A way to publish and fetch OpenPGP keys via HTTPS from the domain of the e-mail address (e.g.

https://openpgpkey.example.com/...). The domain effectively vouches for the key, which makes key discovery more reliable and less phishing-prone than random keyservers.

Conceptually, S/MIME and PGP solve the same problem (encrypt and sign e-mail), but they live in different ecosystems. S/MIME is widely used in companies with central IT that can provision certificates. PGP-based solutions are more common in the open-source and privacy communities and make it easier for individuals to generate and manage their own keys.

WKD-PGP is also how Proton Mail handles e-mail encryption. Proton leans into OpenPGP for standardisation and interoperability with other PGP users and tools. Proton optimises for “use battle-tested OpenPGP so we can work with the rest of the ecosystem,” accepting PGP’s subject-line limitation (for now). Proton also developed its own OpenPGP certificate authority (CA) to improve trust in keys.

Another privacy-focused e-mail service that often comes up in conversations is Tuta (formerly Tutanota). Tuta’s encryption is more “closed” but very metadata-protecting and moving to post-quantum cryptography. They explicitly do not use PGP or S/MIME, citing lack of subject encryption, poor algorithm agility, no Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS), and the EFAIL history, among other reasons. In PGP e-mail encryption, the message body and attachments are end-to-end encrypted, but e-mail subject lines are not. Proton, for example, protects subject lines on Proton’s servers (zero-access), but these are not end-to-end encrypted when crossing the normal e-mail network. This is a limitation of PGP’s current e-mail format, not something specific to Proton.

S/MIME

Unfortunately, the set of trusted certificate authorities (CAs) that issue free, long-lived S/MIME certificates is very small.

As of sources around 2022 - 2025:

- Actalis (Italy) offers one free mailbox-validated S/MIME certificate per account for private use (valid for one year).

- Wikipedia still lists several “free for private use” S/MIME offers (Actalis, WISeKey, short trials from GlobalSign, Secorio, etc.), but many of these are short-lived (1 - 3 months) or positioned as trials rather than stable, long-term options.

If your employer or university runs its own public key infrastructure (PKI), you might get an S/MIME certificate from them, but that usually ties your identity to that organisation and is meant for work or study, not for a private, long-term mailbox on your own domain.

There is also a common catch with (most) free S/MIME offerings, including Actalis: the CA generates your key pair on the server and then sends you a PKCS#12 (.p12 / .pfx) file to import. That means the CA has had your private key at least once, even if they promise to discard it.

Some commercial S/MIME products allow you to generate your own key pair locally and send only a certificate signing request (CSR), which is better for privacy, but this is rare in the free personal segment.

Because of these limitations (few free options, short validity, and server-generated keys), I will not go deeper into S/MIME in this guide and will instead focus on OpenPGP-based options that give you full control over your own keys.

Autocrypt

Autocrypt is designed to make OpenPGP encryption “just work” between normal e-mail users, even if they never think about keys. To keep things simple, it deliberately does not try to detect man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks or spoofing: the key in the header can be silently replaced by an active attacker who sends spoofed mail, and users are not warned when keys change.

This design choice trades strong identity verification for easy everyday encryption. Autocrypt assumes that most attackers cannot reliably intercept and modify all your messages, and that for many users “some encryption most of the time” is still a big improvement over “no encryption at all”.

Autocrypt is mainly supported by privacy-oriented e-mail clients such as K-9 Mail, Thunderbird (with built-in OpenPGP), and KMail. Support is improving, but it is still not as widely deployed as S/MIME in large corporate environments.

Autocrypt also tries to be “automatic”, but the trust story is very different. S/MIME’s trust is rooted in the CA store the client already uses and understands; Autocrypt’s is closer to TOFU (Trust on First Use): “I saw a key in a header once, so I’ll just trust it from now on.”

In practice, this means Autocrypt is great for people who mostly care that their everyday mail to friends and family is encrypted with minimal setup. It is less ideal if you need strong guarantees that you are always talking to the right cryptographic identity (for example, in high-risk or professional threat models).

To verify that Autocrypt is configured correctly in your e-mail client use the “view headers” feature of your e-mail client. This gives you the raw headers so you can inspect them. According to the Autocrypt Level 1 specification, the header has these fields:

Autocrypt: addr=you@example.com;

prefer-encrypt=mutual|nopreference;

keydata=<BASE64 of full public key>Web Key Directory (WKD)

Web Key Directory (WKD) is a way to publish and fetch OpenPGP keys via HTTPS from the domain of the e-mail address (for example: https://openpgpkey.example.com/...).

The domain effectively vouches for the key, which makes key discovery more reliable and less phishing-prone than using random keyservers.

If you use OpenPGP/GnuPG for e-mail security, consider publishing your public key with Web Key Directory.

It is usually much easier than it looks at first. If you followed this guide, you are already sending e-mail from your own domain (for example: user@example.com) and you have a publicly reachable virtual private server (VPS) running Traefik as a reverse proxy.

That is already enough to make WKD-PGP work.

You only need to publish your public key at a specific URL location on your VPS, so that WKD-aware tools can find it. Traefik will simply serve these files over HTTPS like any other static content.

WKD has two publishing modes (“direct” and “advanced”), but both boil down to placing your OpenPGP keys under a

/.well-known/openpgpkey/path on a host such asopenpgpkey.example.comor your main domain. Tools like GnuPG can generate the correct file layout and hashes for you, so you usually do not have to care about the exact URL structure.

When a sender uses a supporting mail client and adds an e-mail address to a message, the client will automatically check whether WKD is set up for the receiver’s domain. If a public key is found, it is fetched and imported into the keyring, allowing secure communication without the user having to search keyservers or exchange keys manually.

Tooling: GnuPG, Kleopatra Certificate Manager, and KMail

The workhorse for OpenPGP encryption is The GNU Privacy Guard, or GnuPG (gpg) for short.

It is a powerful command-line tool that implements the OpenPGP standard.

But PGP is quite involved and comes with many command-line switches that are hard to remember. I personally prefer to use the Kleopatra certificate manager on the desktop. Kleopatra is an open-source certificate manager and graphical front-end for cryptographic services, mainly designed to handle OpenPGP and S/MIME (X.509) certificates. Under the hood, Kleopatra is “just” a GUI for GnuPG, so you can freely mix use of the command line and the graphical interface.

On Windows, Kleopatra is typically installed as part of Gpg4win. On most Linux distributions, it is available as a normal package (often called

kleopatra) and integrates nicely with the KDE desktop. Either way, the keys you create are stored in the same GnuPG keyring thatgpguses.

To create a PGP key for your e-mail account in Kleopatra, go to

File > New OpenPGP Key Pair.... Enter your name and the e-mail address you want to use, then follow the wizard. You should protect your private key with a strong password (passphrase).

After creating the key, export and safely store a revocation certificate and a backup of your private key. A revocation certificate lets you mark the key as invalid if you ever lose control of it or forget the passphrase.

I use KeePassXC as a password manager and as a backup store for my secrets. KeePassXC is just an encrypted container (KDBX). KeePassXC should be a backup/transport vault, not a replacement for GnuPG’s own keyring. Whether this is a “good idea” depends on your threat model:

- You already trust KeePassXC with everything else (online banking passwords, etc.).

- You use a strong master password, maybe a keyfile, and sane KDBX settings.

Pros of this approach:

- You get a central, encrypted backup of your GPG key, protected twice: by the key’s own passphrase and by the KeePassXC database encryption (KDBX uses AES/ChaCha20 + Argon2; with a good master password/keyfile this is strong).

- It is very convenient for restoring keys after reinstalling, setting up new machines, and avoiding permanent key loss (a surprisingly common problem).

The pattern is:

- Store your GPG passphrase as a KeePassXC entry.

- Attach files to that entry (ASCII-armored public and secret key export, revocation certificate, ownertrust backup).

You can use Kleopatra to export the public key (right-click on the key →

Export...) and the secret key (right-click on the key →Backup Secret Keys).

For command-line users, something like this works:# list all your keys gpg --list-keys # public key (ASCII armored): gpg --export --armor 'you@example.com' > you-public.asc # secret key (ASCII armored): gpg --export-secret-keys --armor 'you@example.com' > you-secret.asc # optional: trust settings gpg --export-ownertrust > ownertrust.txt # strongly recommended: revocation certificate gpg --output revoke-you.asc --gen-revoke 'you@example.com'

KMail is the KDE e-mail client. Autocrypt support was added in KDE Gear 21.04, and KMail also implements WKD (Web Key Directory). KMail delegates all Autocrypt-PGP and WKD-PGP related operations to the underlying GnuPG, so you get the same cryptographic engine everywhere.

To enable encryption in KMail:

-

Open

Settings > Configure KMail… > Security > Encryption.

Simply turn on all the OpenPGP-related options-checkboxes (Autocrypt and WKD). For all other values, the defaults are fine; you mostly just need to enable the features. -

Then go to

Settings > Configure KMail… > Accounts.

Select the account you want to use with encryption, clickModify…, then go to theCryptographytab. -

Choose the PGP key that matches your e-mail address.

Enable “Use same key for encryption and signing” so that KMail uses that key for both actions. -

In the Autocrypt section, check all the checkboxes for this account.

And in the “Overwrite defaults” section, also check all the checkboxes in that section.

That’s it: KMail will now use your GnuPG key for Autocrypt-PGP and WKD-PGP, and will try to encrypt mail automatically whenever it can find a key for your contacts.

Make sure WKD lookups are used (GnuPG side): KMail doesn’t speak WKD directly; it asks GnuPG to locate keys by e-mail address, and GnuPG’s

auto-key-locatemechanism decides how (local keyring, WKD, keyservers, etc.). Any MUA that uses--locate-keysbenefits from WKD this way.On most modern GnuPG installations, WKD is already part of the default

auto-key-locatechain. If you want to be explicit:

- Open

~/.gnupg/gpg.confin a text editor.- Add or adjust a line like:

auto-key-locate local,wkd,keyserver

local- check existing keys in your keyring.wkd- query recipients’ domains via Web Key Directory.keyserver- fall back to configured keyserver(s).

Setting up OpenPGP Web Key Directory

The following steps should be performed on your virtual private server (VPS) where Traefik is running.

I assume that the dockerized Traefik lives in /opt/traefik and that you run all commands from that directory.

I will set up the so-called advanced WKD layout, which is only slightly more complex than the “direct” method. The advanced method is good for multi-domain and “WKD as a service” use cases. That matters if you want to serve several e-mail domains with the same VPS/Traefik/home server/Mailu infrastructure. In that case, all domains can be served by the same backend, while each e-mail domain still has its own WKD URL pattern.

For each of your mail domains you need a DNS A record (and optionally AAAA for IPv6; CNAME can also work) similar to openpgpkey.mail.example.com pointing to your VPS IP address.

The target directory structure will look like:

./wkd/

nginx.conf

public/

.well-known/

openpgpkey/

mail.example.com/

policy

hu/<32-char-hash-for-user> # binary key (gpg --export)

example.com/

policy

hu/<32-char-hash-for-user> # binary key (gpg --export)

abc.xyz/

policy

hu/<32-char-hash-for-user> # binary key (gpg --export)We start with the setup for the mail.example.com domain:

mkdir -p ./wkd/public/.well-known/openpgpkey/mail.example.com/hu

touch ./wkd/public/.well-known/openpgpkey/mail.example.com/policyThe policy file can be empty.

The <32-char-hash-for-user> and the binary key can be generated via:

gpg-wks-client --print-wkd-hash user@mail.example.com

# or

gpg --with-wkd-hash -k user@mail.example.com

# Use the hash that you see on screen as the file name of the binary public key:

gpg --export --export-options export-minimal \

-o /opt/traefik/wkd/public/.well-known/openpgpkey/mail.example.com/hu/<32-char-hash-for-user> \

user@mail.example.comNext, create a docker-compose-wkd-for-mailu-domains.yml file in the /opt/traefik directory:

services:

wkd_nginx:

image: nginx:1.29.3

container_name: wkd_nginx

restart: unless-stopped

networks:

- main

volumes:

# WKD static files:

- ./wkd/public:/usr/share/nginx/html:ro

# nginx vhost / WKD-specific config

- ./wkd/nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/conf.d/wkd.conf:ro

labels:

- traefik.enable=true

- traefik.docker.network=main

# Route WKD HTTPS traffic from Traefik to this container

- traefik.http.routers.wkd.entrypoints=web-secure

- traefik.http.routers.wkd.rule=Host(`openpgpkey.mail.example.com`)

- traefik.http.routers.wkd.tls=true

# Use the Cloudflare dns-01 resolver

- traefik.http.routers.wkd.tls.certresolver=cf-dns

# Service (nginx listens on 80 in the container)

- traefik.http.services.wkd.loadbalancer.server.port=80

networks:

main:

external:

name: traefik_defaultAnd an nginx.conf file at ./wkd/nginx.conf:

server {

listen 80 default_server;

server_name _;

# WKD files live under:

# /usr/share/nginx/html/.well-known/openpgpkey/mail.example.com/...

root /usr/share/nginx/html;

# Serve WKD content for advanced method

#

# For user@mail.example.com the client will fetch:

# https://openpgpkey.mail.example.com/.well-known/openpgpkey/mail.example.com/hu/<hash>?l=user

#

# Files you need on disk:

# .well-known/openpgpkey/mail.example.com/policy (can be empty)

# .well-known/openpgpkey/mail.example.com/hu/<hash> (binary public key)

#

location /.well-known/openpgpkey/ {

# Serve as binary blob (recommended for WKD)